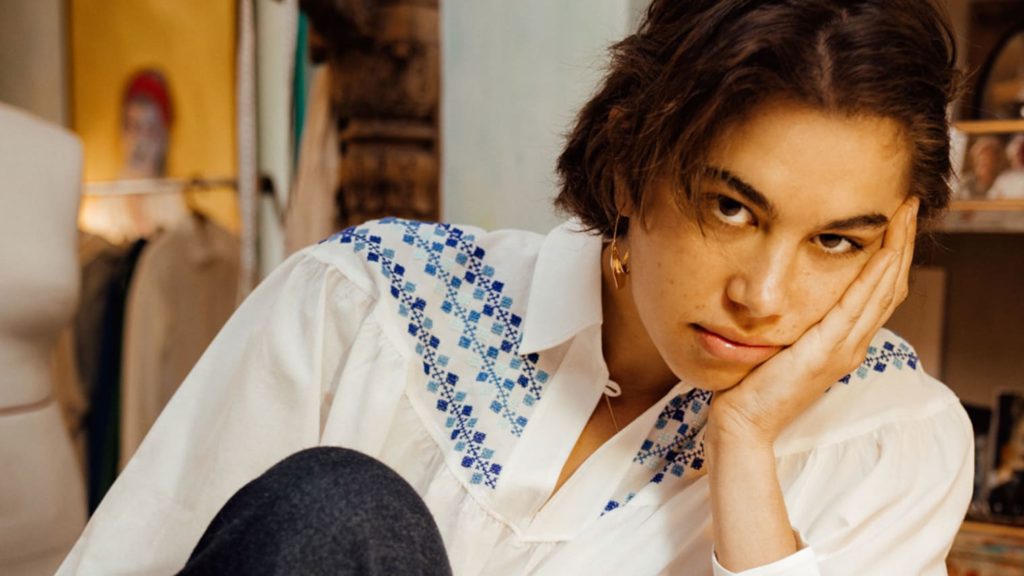

On August 2, 2020, Larissa von Planta packed up her life in Beirut, where she had worked as a sustainable fashion designer for five years. Beirut’s economic situation had worsened since she had arrived in 2015, causing many of her friends to leave the city. After von Planta’s mother died in May of the same year, she felt compelled to return to London.

Two days after von Planta arrived back home, news broke of the devastating explosion which destroyed Beirut’s city center. The huge blast, reportedly caused by 2,750 metric tons of ammonium nitrate stored in a warehouse in Beirut’s port, killed more than 200 people and caused colossal damage to the city’s infrastructure.”

A friend of mine messaged me and asked whether I had seen what was happening in Beirut,” von Planta, 27, explained during a phone interview. “I went on Google and saw the flaming port and then the explosion a couple of seconds later. I couldn’t even register what that meant — I thought Beirut was going to be completely flattened. I had never seen anything like that before.”

Feeling powerless in London, von Planta set up a Go Fund Me Page (which accumulated £30,000 ($42,000) for local repairs, friends and casualties) and contacted Meike Ziervogel, the CEO of a local non-profit called Alsama Project, which runs women’s empowerment schemes. Von Planta had collaborated with Ziervogel before and worked with one of Alsama Project’s branches, Alsama Studios.

Run by Fatima Khalifa, who fled Syria with her children in 2012, Alsama Studios provides embroidery work for Syrian and Palestinian refugee women. The studio operates from one of Lebanon’s refugee camps, Bourj al-Barajneh, where Khalifa and the other embroiderers live.

According to Khalifa, the refugee camp is unsafe — there is gun violence, drugs and the health conditions are “appalling.”

“As refugees you don’t have another choice,” explained Ziervogel during a joint video interview with Khalifa. “Many of the refugees come in illegally and they live under continuous fear of being sent back, especially the young men. The refugee camp is outside the law (in Lebanon), so while you’re in the camp, the government can’t get you.”

“I wanted to provide work for these women,” von Planta said. “I knew from Meike that the embroiderers had slumped into a huge depression. They live such precarious lifestyles; they aren’t Lebanese citizens so there’s a lot of instability. They can’t go back to their countries. I wanted to make sure work was coming in so they had one less concern.”

“Before the explosion, there was the hope that the (economic situation) would get better,” added Zoiervogel. “But seeing how the politicians dealt with the explosion — or didn’t deal with it — made us realize that the country was going to slide down even further. It was a big shock to the women and Khalifa.”

“We needed a simple idea,” said von Planta, who trained at Central Saint Martins, a prestigious fashion and creative university in London. “We didn’t want to make anything new. We just asked our friends to send clothes to be embroidered.” When von Planta returned to Lebanon on August 20, she brought 30 pieces of clothing — from denim jackets to kaftans — to be embroidered by the women at Alsama Studios.

Some people asked for specific colors while others preferred the element of surprise and gave no instructions. “The embroiderers loved it because some people came with colors that they’d never think would go together.” “The most exciting part is the collaboration,” said Khalifa. “Larissa is a very impressive designer so she comes with her ideas, then the women bring their designs and the customer as well. In this way, they create unique pieces.”

Within three months, the 30 pieces were returned, complete with intricate embroidery and Syrian or Palestinian motifs. “The motifs are very specific to a location and influenced by the agriculture and surroundings,” explained von Planta. “Each motif represents something; there are plants, stars and a sinister one that depicts barbed wire, representing how things have changed.

“The upcycling initiative was so successful that von Planta and Khalifa continued working together, creating the project LVP x Alasma Studios. Now, 200 pieces have been embroidered by the refugee women, with the money going towards the workers’ wages and various business costs.

The 35 embroiderers enjoy seeing photographs of customers wearing their upcycled garments. “Suddenly seeing the garment in the outside world, when you’ve been working on it for 10 days inside the camp, is almost more valuable than the money,” said Khalifa. “It’s valuable to see that support.”

“There’s a real closeness between the customer and these women in Beirut living these totally different lives,” said von Planta. “You’re impacting them just by sending one piece.” Some of the refugee women send personalized notes in Arabic along with the garments.

Alasama Studios is a haven for Khalifa and her team of embroiderers. “Alsama is very much a place of safety,” said Khalifa. “The women can come and they can talk about things that they can’t talk about in their homes.

“Khalifa recruits women who are looking to “better themselves” and give back to their community. “A lot of the women have been living with depression for many years,” she explained, who said she sank into a deep depression when she arrived at the refugee camp; she had no electricity or light and she couldn’t afford to send her three boys to school.

“Most of the women, myself included, have lost family members in the war or left family behind,” said Khalifa. “Alsama is a surrogate family and gives the women strength so they can inspire the next generation, their children, to leave the camp one day.”

“The LVP x Alasama project has given the studio hope that the situation (in Beirut) can improve,” she added. “It’s not just about earnings — (the project) has given the women psychological support.”

Article Credit: edition.cnn