Purposefully kept out of the dairy business because of their social position, Dalit women often represent some of the most oppressed individuals in the country.

What does it take to get a glass of fresh milk every day? For many of us, not much. It is delivered to the doorstep.

However, it is also true that for millions, this much-needed source of calcium is a rarity. Even though the truth is that there are thousands of women ready to sell the milk, but find no buyers.

Such strange situations are the true face of poverty, which is not so much a lack of money as a series of systems that ensure certain sections, and especially genders, remain in chronic poverty.

As an Indian, irrespective of whether you live in the plushest of urban suburbs, or in the most rural parts of this country, poverty is never too far away from you.

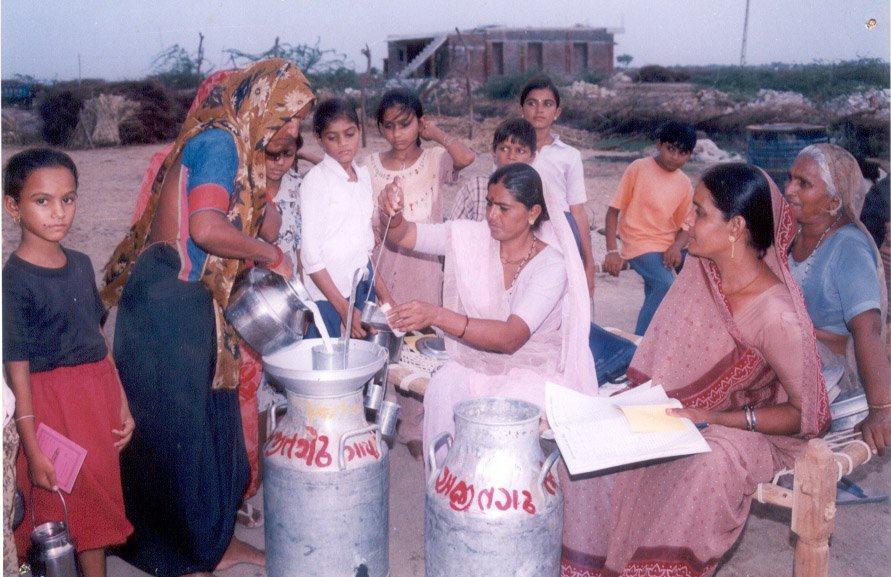

For representational purposes. Source: Wikimedia.

Its uncomfortable presence appears in the beggar ignored at a traffic signal, the slums that exist next to highrises, the homeless person slouched up against a public wall, the manual scavenger who cleans our drains, and the ragpicker wading through waste to afford less than a square meal.

India is home to the highest number of people living in poverty across the world – a staggering 400 million. That is 75 million more people than the entire population of the United States of America, or the equivalent of all the people living in Germany, France, the United Kingdom, Italy, Ukraine, Poland, Romania, the Netherland and Belgium together.

And all of this is fundamentally worse if you are a woman. The youth literacy rate from the last census is nearly 15 percent lower for women in India at 74%, according to the UN. Put the figure against the 99.2% of the developed world and the ugly stark reality is hard to deny.

Development and women empowerment are not mutually exclusive. In fact, the latter is indicative of the former. Millions of Indian women are illiterate, and this is their cross to bear.

Millions have yet another burden. India banned caste-based discrimination in 1955, but centuries-old attitudes persist, and lower-caste groups including Dalits are among the most marginalised communities.

Poverty levels are the second highest among Dalits at 65.8 percent, who are after India’s tribal population at 81.4 percent.

Landless Dalits are at the bottom of India’s age-old social hierarchy, making them vulnerable to discrimination and attacks by upper-caste Hindus, including by those who regard cows as sacred.

Coming back to our introduction, it bears repeating – while there is a belief that alleviating poverty is merely a question of distributing wealth, time and again it has been proven that this is not the case. Unless the cause for poverty – factors like society and exclusion – are considered, merely doling out money is like jogging in place. A lot of effort but going nowhere.

And it is to highlight how such factors affect everything; we once again consider something mundane as a glass of milk.

Good milk is always in demand, so maintaining a dairy farm can be a great way to earn a livelihood – as Amul proved.

And yet, purposefully kept out of the dairy business because of their social position, Dalit women often represent some of the most oppressed individuals in the country.

To end this cycle of neglect and poverty, NGO CARE India led an initiative to help Dalit women in Tamil Nadu break into the profitable dairy industry.

A dairy value chain initiative was set in place to supplement the conventional microfinance approach to value chain financing. This had two advantages – it allowed Dalit women to gain yet another means of self-employment, and by passing over the traditional biases against them from the usual milk collectors, allowed them to join the dairy business without prejudice. Though this did not end discrimination against them directly, it helped alleviate their poverty, thereby eventually empowering them.

“Dalits were kept out of the food chain. Milk booth collectors would pass by their neighbourhoods collecting milk, but refuse to take it from them,” says Bharati Joshi, Technical Director Livelihood, CARE India, referring to locations in Tamil Nadu.

“We trained the women to become excellent dairy farmers. A financial institution stepped forward and sponsored this initiative. As a result, today even private milk companies come to their households and collect milk from them,” Bharati explains.

A dairy value chain initiative was set in place to supplement the conventional microfinance approach to value chain financing.

The project began in 2012, implemented in Kattumanarkoil and Srimushnam blocks of Cuddalore district in Tamil Nadu and aimed at substantially increasing the number of milch animals, establishing feed shops, fodder plots, para-vet services, facilitate linkages with banks, animal husbandry department of the state government, and dairy units.

All the interventions were designed on a revenue generation model to not only enable the activities to sustain themselves, but also to contribute to the sustainability of the SHG federation in the long run.

There was an increase in the number of women engaged in dairying with an increase in animal stock too. About a quarter of the participants were first-time dairy entrepreneurs, exposed to a sector that was capable of giving them a fair wage and a better standard of living.

This initiative, which introduced innovative financial products across the chain, enabled access to feed, fodder and milk markets through milk collection centres and milk sale points. It has helped over 2000 women improve their returns from dairy – while preventing the caste system from keeping them down.

There was an increasing evidence of breaking gender stereotypes and promoting gender transformative outcomes in the value chain.

Rising income levels can free people from the below poverty line category, but it hardly guarantees a significantly improved standard of life. The poor also depend on community-level infrastructures such as primary and secondary educational institutions and health-care networks. The effort cannot only be state-driven, but community-aided too.

It also means tackling the ugly monster called caste in this country. Alleviation cannot come only in the form of material upliftment. For it to be holistic, the problem must be attacked from all quarters.

While there is much to marvel over in India, there is an equal amount of despair that must go – poor health care, pitiful educational institutions, untouchability, feudalism, bonded labour, extreme caste and gender oppression and exploitation, and more.

Since our independence, India has hit milestones against extreme poverty, but the harsh reality is that about 680 million of our citizens live with various forms of deprivation.

However, sometimes this can be changed by looking at the issue from a different angle – and finding the real reason why large sections remain oppressed.

In a country that battles casteism, patriarchy, unequal opportunity, and domestic violence among a host of other issues beating down its women, the existence of private organizations like CARE India is as much a necessity as comprehensive state programs are.

The role of civil society as a watchdog increases transparency and the participation of people in the development process.

While the Government of India makes commitments about Millennium/Sustainable Development Goals, the work of such organisations is crucial to achieve time-bound targets and to bring about more effective work.

This article is a part of The Better India’s attempt to drive conversation around the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and where India stands with regards to meeting these goals. Many organisations across the country are helping India proceed towards fulfilment of these goals and this series is dedicated to recognising their efforts and the kind of impact they have created so far.

Article Source: The Better India