After years of debate, FSSAI has chosen to go with a controversial 5-star system to rate the nutritional value of packaged foods. Now it must figure out how to generate consumer awareness, buy-in from industry, and set nutritional thresholds for its new system.

India’s food industry is batting for the regulator’s decision to paste ‘health stars’ on ultra-processed food packs. Consumer groups, though, want more in-your-face warning labels

IIM-A study conducted in over 20,000 people ranks health stars and warning labels in close competition, but recommends health stars

FSSAI’s scientific panel feels the regulator has jumped the gun. It is now mulling ways to avoid rewarding more stars to ‘unhealthy,’ food

Implementing the revised packaging will require buy-in from big and small companies, incentivisation and a massive awareness drive. Is India ready yet?

Seeing stars: FSSAI’s food labelling decision opens a can of worms

On 15 February, the conference hall of the Food Safety and Standards Authority of India (FSSAI) hosted a meeting that could have serious consequences on the overall health of India’s population. The latest in a series of fiercely contested discussions, the meeting was meant to achieve consensus on how best to label packaged food to help consumers make healthier choices.

While previous meetings were deadlocked, this time, the FSSAI had an ace up its sleeve. A team of professors from the Indian Institute of Management, Ahmedabad (IIM-A) were ushered in to discuss the results of a pan-India survey. The survey was to identify what sort of labelling most effectively conveyed nutritional information. Having polled 20,564 respondents, the team from IIM-A pointed to one clear winner—Health Star Ratings, or HSR.

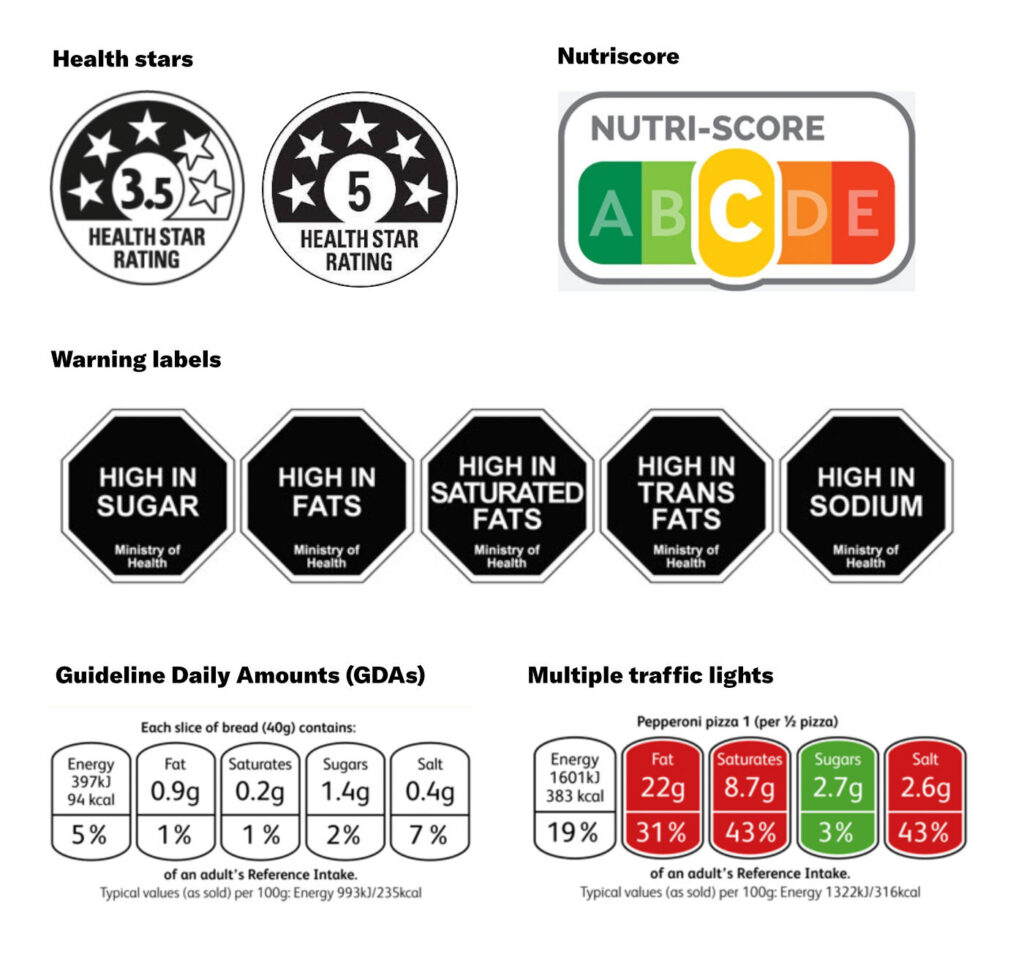

HSR rates foods on a five-star scale based on factors such as energy, saturated fat, sodium, total sugar, and healthier aspects such as protein, natural ingredients, and the like. The final rating is decided by an algorithm that takes into account all this, with healthier food receiving higher ratings. These would be displayed on the front of the packaging.

India isn’t alone in going the HSR route. Australia, too, adopted the HSR system as far back as 2014. But despite the Australian government’s best intentions, things haven’t quite gone to plan.

Mark Lawrence, professor of public health nutrition at Deakin University in Australia, told The Ken that 73% of ultra-processed food on supermarket shelves displayed ratings of 2.5 stars or higher. Effectively, said Lawrence, who studied the star rating implementation, the ratings failed to convey anything of value—nutrition-wise—to the consumer.

Worse, HSR also created a ‘health halo’ effect, which is the perception that a particular food is good for you even when there is little or no evidence to back this. Indeed, there were numerous instances where decidedly unhealthy products received the highest possible health rating.

Seeing stars: FSSAI’s food labelling decision opens a can of worms

Despite this precedent—or perhaps because of it—there was widespread support for the HSR approach among the 23 stakeholders present at the FSSAI meeting. Seventeen of these were major food and beverage companies, including Coca Cola, Dabur, ITC, Kelloggs, Nestle and Haldirams.

Many members of FSSAI’s own expert scientific panel, however, were aghast. “We had insisted that a copy of the IIM-A study be shared with us for internal consultation before being presented to the larger group of stakeholders. This was so we could deliberate on it and prepare our comments, but we were given no time,” said one member of the panel. They requested anonymity for fear of repercussions.

Seeing stars: FSSAI’s food labelling decision opens a can of worms

The stakes at play here are anything but trivial. Currently, 5.8 million Indians die every year from chronic diseases such as cancer, diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases. “Most of these deadly diseases, although hard to treat, may be prevented by modifying diet and transforming the food industry,” Ashim Sanyal, chief operating officer of Voluntary Organisation in Interest of Consumer Education (VOICE), told The Ken. Sanyal is also a member of FSSAI’s stakeholder committee.

FSSAI CEO Arun Singhal, though, appears to have no such apprehensions about HSR. Once the study was presented, he wasted no time, suggesting that the decision to include HSR on packaged foods be introduced as a draft regulation. The decision is all the more contentious since FSSAI wants to make HSR voluntary for manufacturers for a period of four years.

“After necessary approvals from the Health Ministry, the draft regulation will be notified in a gazette and then be open to public comments. The entire process of finalising this into a law may take a whole year,” Singhal said.

Seeing stars: FSSAI’s food labelling decision opens a can of worms

FSSAI is already moving on to implementing HSR. It has instructed its scientific expert group to begin working on algorithms to calculate HSR. These will be customised to the Indian context in an attempt to avoid the Australian debacle, the expert panel member quoted above said. “Take for instance, kaju katli (a cashew-based milk sweet). No matter how many cashews you add, it has such mind-bogglingly high levels of sugar it can never attract more stars. Similarly, Gulab Jamun, (an Indian sweet made of deep-fried refined flour dumplings dunked in sugary syrup) attracted 1.5 stars,” pointed out the expert member quoted above.

Health Stars versus Warning Labels

Since chips and biscuits are among the most commonly consumed junk food in the country, IIM-A designed its survey around them. Researchers designed a blue potato chips packet (visually mimicking the popular ‘Lays’ brand) and a yellow biscuit packet based on the packaging of the ubiquitous Parle-G biscuit brand. No brand, however, was mentioned on the packaging.

Instead, the packaging sported different forms of front of package labelling (FoPL), including HSR, warning labels, nutriscore, etc. Field personnel showed these to respondents, using questionnaires to determine the efficacy of each of these methods in communicating nutritional information and warning consumers about unhealthy foods. IIM-A declined to share the questionnaire with The Ken.

While the IIM-A team ultimately backed HSR, the survey results aren’t nearly as flattering as one would expect. Respondents who, as part of the study’s design, were manipulated to believe that chips and biscuits were healthy, were more strongly influenced to avoid unhealthy foods by warning labels than HSR. Even among respondents who were under no illusions about the health risks of junk food, warning labels were a more effective deterrent than HSR, the study noted.

Overall, health stars and warning labels found the most broad-based support across occupations, the study noted. However, despite warning labels scoring higher on average across the six parameters IIM-A was tracking, HSR came out ahead on more parameters, leading the group to ultimately recommend HSR.

“We were asked to recommend only one option for FoPL. If the objective is ease of identifying, understanding, and a change in purchase intention, we recommend health stars,” Arvind Sahay, professor of marketing and international business at IIM-A, told The Ken.

One oft-cited reason why HSR often wins out, is that star ratings are commonly used across industries, making the system widely recognised. However, as Sanyal pointed out, electronic appliances and ultra-processed foods are incomparable. “Nutrition science is way more complex than that,” he said.

Those like Sanyal prefer the use of warning labels. These text-based labels provide in-your-face nutritional information. A packet of chips, for instance, may be simply labelled as “high in fats and salt”, eradicating any ambiguity in the mind of the consumer. Studies also back up their effectiveness.

One study conducted by Mumbai-based Indian Institute of Population Sciences (IIPS) between January and March 2022 showed that 61% of participants who were shown warning labels could identify all excess nutrients in the food. Only 45% of those shown HSR could correctly interpret them. (It should be noted, though, that the IIM-A study was far larger—over 20,000 respondents across 20 states, whereas the IIPS study only surveyed 2,869 adults across six states. Urban and rural populations were part of both studies.)

IIPS, however, is far from the only body that’s at odds with IIM-A’s recommendations. Doctors at the Institute of Liver and Biliary Sciences, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, and multiple consumer groups have all cried foul. They argue that instead of following the Australian route, India should aim to replicate the warning labels implemented by South American countries such Chile and Uruguay.

Marcela Reyes, assistant professor at the University of Chile’s Institute of Nutrition and Food Tech, told The Ken that it took Chile nearly a decade to introduce warning labels on packaged food. Reyes and her team analysed all naturally occurring food using the US Food and Drug Administration’s data, and arrived at a median of 10 grams of sugar per 100 grams as a ‘healthy’ parameter. “Any food crossing this threshold was stamped as high in sugar in bold black hexagonal symbols,” Reyes said.

Unsurprisingly, food and beverage majors—including Kelloggs, which is part of FSSAI’s stakeholder group—were against the move. Kelloggs even dragged the Chilean government to court, but was ultimately unsuccessful in its efforts. The effects of Chile’s warning labels are there for all to see. Far removed from the delusional ‘health halo’ effect seen in Australia, Chile has seen the sales of sugary drinks decrease by 23%, said Reyes.

Setting thresholds

IIM-A’s Sahay told The Ken that the purview of their survey was to identify ease of identification of labelling. It does not probe the underlying reasons for why HSR or warning labels may be a better fit for the Indian population. Where Sahay’s problems end, however, the problems for members of FSSAI’s scientific expert group begin.

If the new HSR system is adopted, manufacturers must upload the nutritional information of all their products on the Food Safety and Compliance System (FoSCoS), a licensing platform run by FSSAI. “The platform will automatically calculate the number of stars to be assigned on the basis of the algorithm, and provide artwork to the companies to revise their labels,” Singhal explained. FSSAI, though, may be jumping the gun.

The body’s ten-member scientific panel of nutritionists, most of them PhDs from various Indian universities, are hard at work analysing various food products on supermarket shelves. Like Reyes and her team in Chile, they too are attempting to identify thresholds for ‘healthy’ levels of fat, sugar, and sodium in foods and beverages.

For instance, a packet of Parle’s Hide and Seek biscuits has 32.2 grams of sugar per 100 grams. Currently, this would be deemed unhealthy as per the World Health Organisation’s recommendations of no more than six grams of sugar per every 100 grams. The expert group is proposing a sugar threshold of 20 grams per every hundred grams of the snack—over 3X higher than WHO’s standards. Currently, there is a tug of war between the industry and FSSAI on upping these thresholds, as documented in the minutes of the latest FSSAI meeting, which The Ken has accessed.

Developing realistic thresholds will be crucial to implementing any sort of labelling system—especially with Indian sweets and snacks such as gulab jamuns or namkeen being major offenders for sugar and salt, respectively. These experts now face a classic chicken and egg situation. One of the expert members in the scientific panel said that FSSAI should have waited until these thresholds were set in stone before announcing the implementation of HSR.

Following the Australian debacle, FSSAI’s Singhal told The Ken that the expert group is very closely analysing products to design a HSR algorithm that recognises India’s unique needs. A nutrition expert who is part of FSSAI’s expert group told The Ken that it is unlikely that most potato chips would manage a rating of more than half a star.

The expert, however, was apprehensive about how things may play out. For one, they said, there’s the worry that food and beverage companies simply misrepresent the amount of salt, sugar, and fat in their labelling. In some cases, the expert said, products had more sodium than what was declared by the manufacturer. “We need to be vigilant about what companies are self-declaring on labels. They use multiple names on the pack as there are no regulations yet on reporting all ingredients in one place,” the nutrition expert said.

According to the expert group’s preliminary analysis, which The Ken accessed, even a bar of dark chocolate with fruits and nuts will attract a half-star rating because of its high sugar content. “We are mindful of the fact that the mere addition of a few nuts should not mask the negative nutritional content (high sugar, in this case) of the food,” Singhal explained.

Similarly, instant noodles also attract a half-star rating. “Ready to eat soup mixes and soupy noodles are the worst due to the heavy presence of preservatives, anti-caking agents, and flavour enhancers,” said the nutrition expert quoted above.

Sins of the sweet tooth

Even as FSSAI barrels along in its attempt to implement nutritional thresholds and HSR, the food and beverage industry is waiting and watching to see how they will be impacted.

Take digestive cookies, for instance, which are generally marketed as healthy. According to the preliminary analysis accessed by The Ken, these biscuits would only garner a 1.5-star rating. This is because of their high fat and sugar content, with their high fibre the only saving grace.

Will these ratings actually impact large manufacturers such as Parle? That remains to be seen. Parle, for instance, runs a Rs 15,000 crore ($1.97 billion) operation, selling 100,000 tonnes of biscuits—including a premium range of digestive cookies and Parle-G. To get the cookie format right—which is softer in mouthfeel—manufacturers have to resort to a high-fat recipe, said Krishna Rao, senior category head at Parle Products. “None of the digestive cookies can be ‘healthy’. There is always a compromise,” said Rao.

Rao said that the company will comply with FSSAI’s regulations—be it warning labels or health stars. However, there is no chance that Parle will reformulate its traditional Parle-G biscuit recipe (loaded with sugar and carbs) since it’s a runaway favourite across economic classes.

Consumers are accustomed to the taste of these biscuits. No matter what FOPL, most will continue to buy it. However, it is a good thing that it creates awareness among those who purchase it

KRISHNA RAO, SENIOR CATEGORY HEAD, PARLE PRODUCTS

Even as the HSR system is turning out to be neither carrot nor stick for large manufacturers, its value to consumers is also questionable, pointed out Delhi-based paediatrician Arun Gupta. “What would 1.5 stars say about a digestive biscuit—how much sugar is in it and what are the additives in this—to a borderline diabetic who chooses to consume it, thinking it is a better alternative?” asked Gupta, who is also the convenor of the Nutrition Advocacy in Public Interest (NAPi). NAPi has even approached the Prime Minister’s Office to overturn FSSAI’s decision.

Processed gluttony

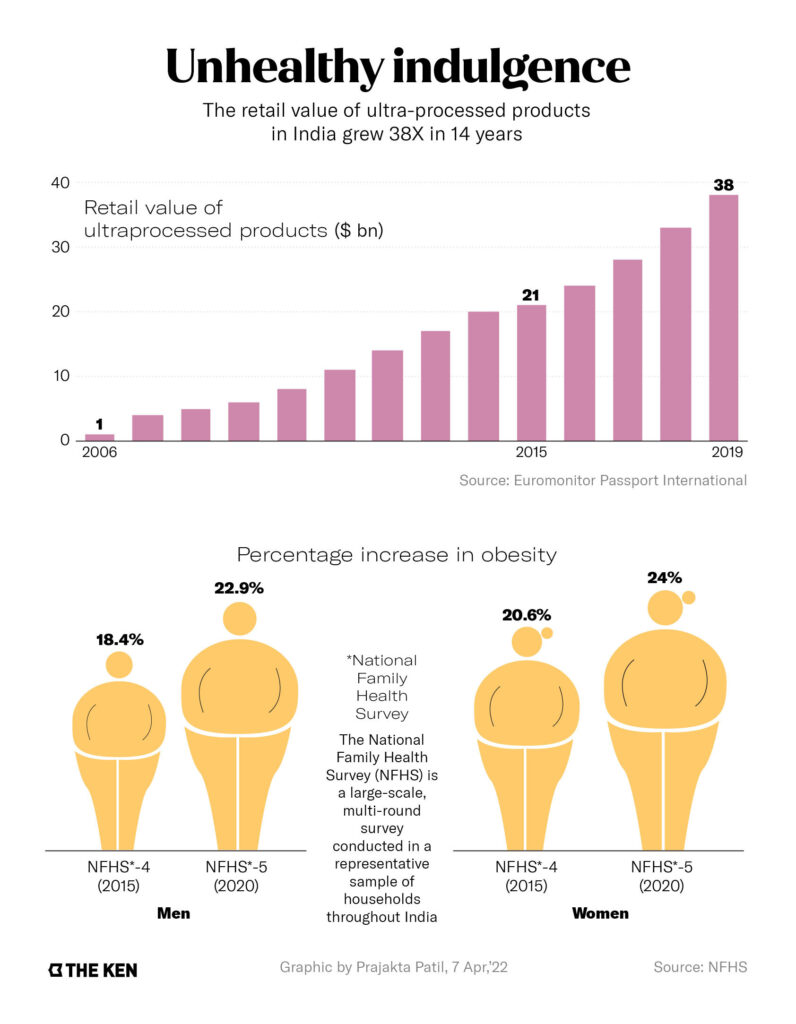

According to Euromonitor data, sales of ultra-processed food in India has increased from 2 kgs per capita in 2005 to 6 kgs in 2019. By 2024, this is expected to reach 8 kilos. Similarly, the sale of beverages has gone up from less than 2 litres in 2005 to about 8 litres in 2019, and is expected to grow to 10 litres by 2024.

And while big brands may comply, the initial voluntary nature of the HSR regulations will find few takers among smaller manufacturers. Prabhu Gandhikumar, founder of TABP Snacks and Beverages, explains that this change could force a company with 10-15 products to make a one-time investment of Rs 8-12 lakh ($10,000 – 16,000) to implement packaging with the HSR. “For a company that has a turnover of Rs 1.5-2 crore ($197,000 – 263,500), that is almost 10% of revenue. What are the incentives for smaller companies to adopt FoPL?” Gandhikumar wondered.

Despite these unresolved issues, FSSAI is forging ahead. The success of this programme, though, will ultimately come down to three things—enforcement, incentivisation, and awareness. The first, to ensure manufacturers comply in both letter and spirit. The second, to ensure even smaller players come on board. And awareness, so that the HSR has its intended effect—helping consumers make healthier choices. The battle to protect India from junk food has only just begun.

Article Credits: The Ken

Pingback: Kellogg’s Splits Into 3 Separate Companies, And One Is Fully Plant-Based - SLSV - A global media & CSR consultancy network