Global warming is driving dangerous and disruptive flooding in underground rail systems around the world. Flooded tunnels and stations have disrupted service and stranded passengers in Boston, London, San Francisco, Taipei, Bangkok, Washington, D.C., and a host of other cities in recent years.

But the problem has taken on added urgency this summer, with multiple, high-profile subway floods driven by summer rainstorms.

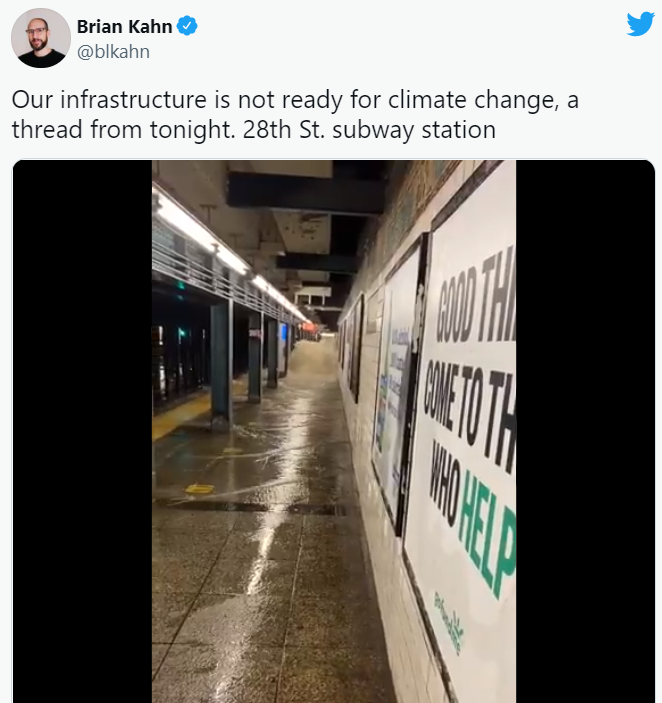

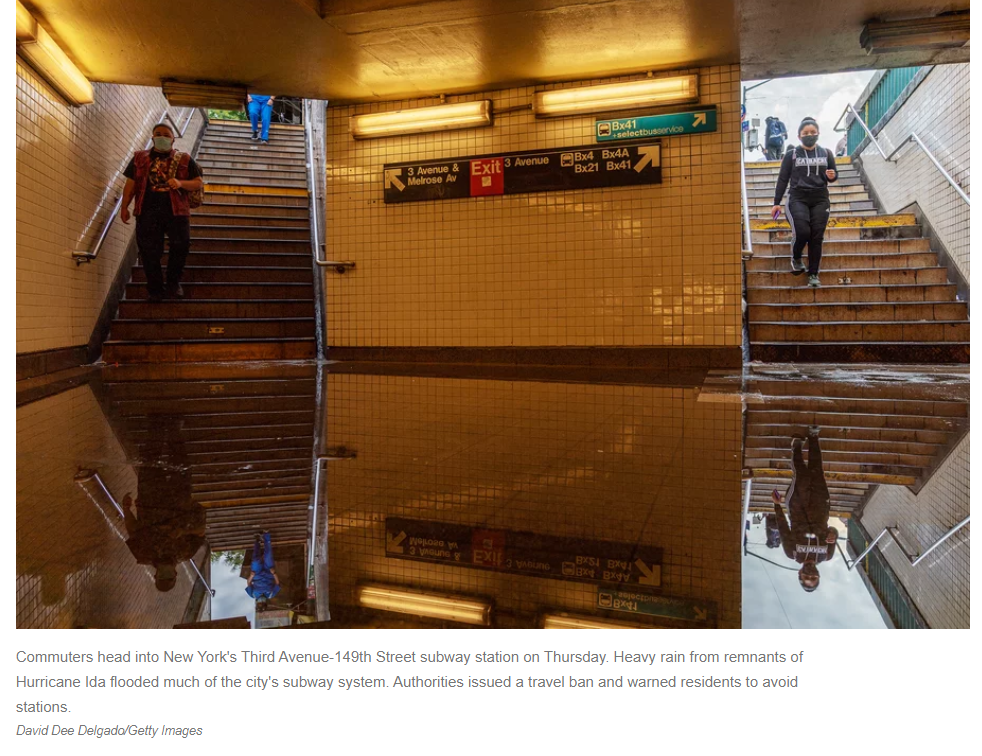

Overnight, the remnants of Hurricane Ida flooded much of the New York City subway. Mayor Bill de Blasio issued a travel ban and warned residents to “stay off subways” as up to 10 inches of rain fell in some parts of the region in a matter of hours.

It is the third time New York’s subways have flooded this summer and the first time the National Weather Service issued a flash flood emergency warning for the city. Heavy rain has also repeatedly swamped underground tracks in Boston.

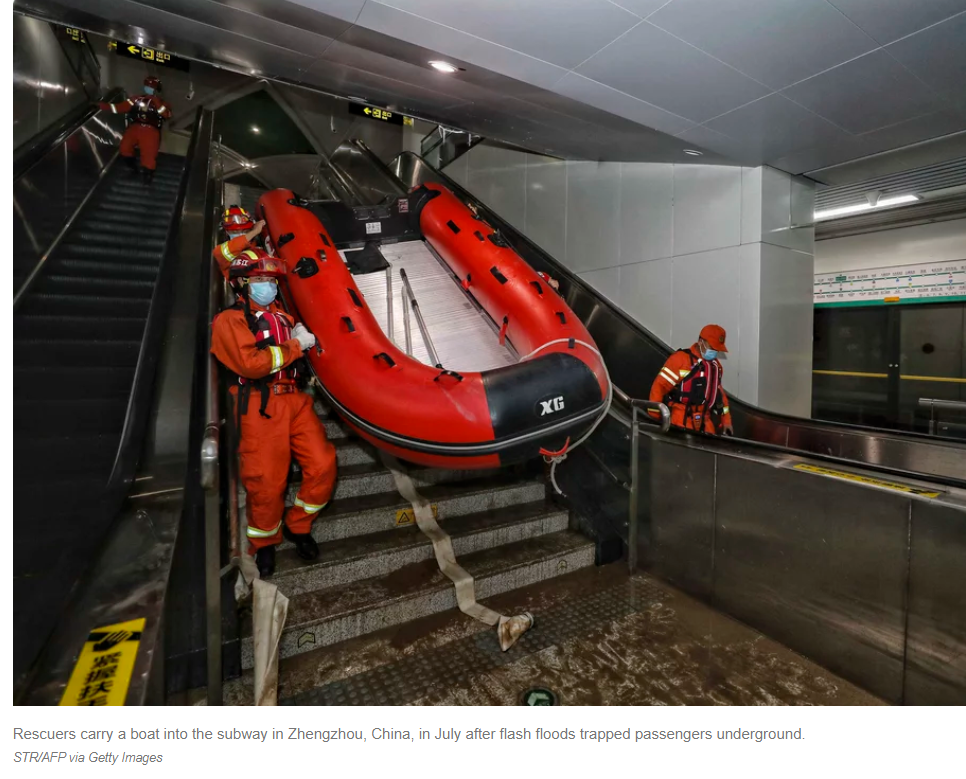

Elsewhere, subway floods have turned deadly. In July, 13 passengers died in Zhengzhou, China, after flash floods trapped them. Harrowing videos showed people struggling to breathe a shrinking pocket of air as the water rose.

“None of us had seen people with water up to their necks, standing in underground trains,” says Slobodan Djordjevic, an engineer at the University of Exeter who specializes in flooding of underground train systems. Djordjevic has spent much of his career studying floods in subway tunnels. But he says what he saw happening in China shocked him. “I actually considered whether this was even real.”

In China and around the world, the culprit is climate-driven torrential rain. Zhengzhou received about a year’s worth of precipitation in just one day. Earlier this summer, the remnants of a tropical storm dumped a month’s worth of rain on New York City in the span of an afternoon. Dozens of subway systems around the world have experienced flooding, Djordjevic says, and he estimates it’s likely hundreds of thousands of passengers have been directly affected.

That has created tension between the need to provide reliable, low-emissions mass transit options and the growing cost of maintaining underground transit in a wetter world. Keeping water out of tunnels and stations is expensive, especially in places with aging, leaky subways built for a 20th century climate.

Some help could come from the federal government. The infrastructure bill moving through Congress allocates $66 billion for rail — a huge infusion of cash that could help fund retrofitting of old subway systems to keep water out and the building of new train lines in places that currently depend on cars.

“Every city should have a comprehensive review of flood risk for the underground system,” Djordjevic says. “Looking ahead, authorities need to think very carefully about where they want to build new lines, new stations, new tunnels.”

Many Asian cities are ahead of the curve

Many U.S. cities are a decade or more into adapting their subway systems to a wetter climate. In Boston, the transit authority has started waterproofing stations and protecting tracks that are vulnerable to sea level rise. After Hurricane Sandy flooded miles of subway tunnels, New York poured millions of dollars into flood control for the nation’s largest underground rail system. In Washington, the transit authority has spent millions of dollars waterproofing leaky tunnels and plans to spend even more to keep water out of vents and station entrances.

“We are investing more in water mitigation today than we ever have,” says Andy Off, executive vice president of capital delivery for the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority. The authority also has an emergency flood response. A unit tracks inclement weather so that flooding hot spots can be monitored and workers can put out sandbags and check underground pump stations before the water arrives.

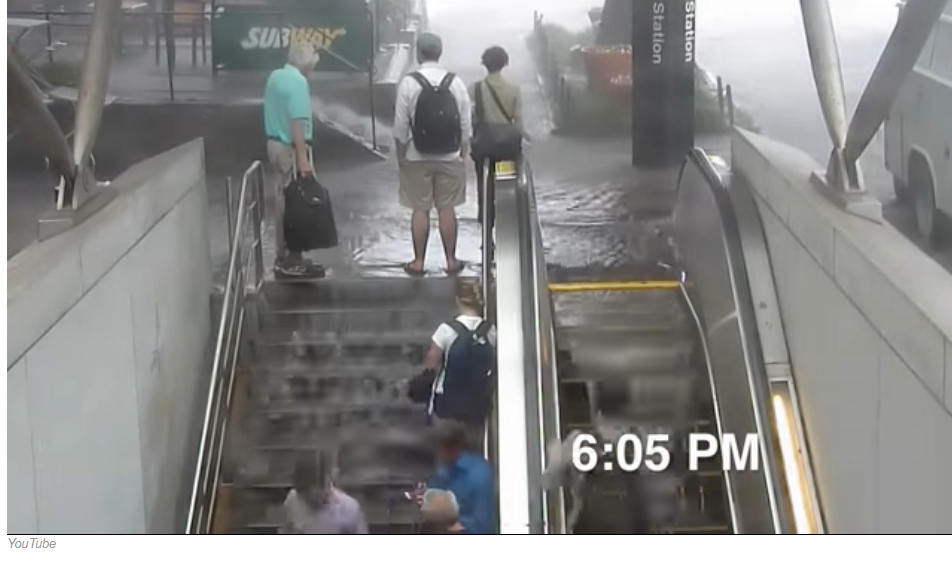

But keeping the water out is a constant battle. Much of Washington metro system was built nearly 50 years ago, and the subways in New York and Boston are even older. Air vents are flush with the sidewalk or street, which makes it easy for water to flow in. Many station entrances are in low-lying places or are constructed in ways that funnel water from the street down stairs or escalators.

“Older systems were designed for the climate of the past,” says Tina Hodges, a former analyst at the Federal Transit Administration who wrote a 2011 report about climate risks to public transit in the United States. “In the Northeastern United States, which is home to some of the oldest and largest transit systems in the country, there’s already been a 67% increase in the heaviest precipitation.”

The same is true in many European cities, including London and Berlin. In recent years, passengers have captured strikingly similar videos of water cascading into subway stations in cities thousands of miles apart.

Newer subway systems in flood-prone parts of Asia may offer clues about how to adapt. As this summer’s disaster in Zhengzhou made clear, Asian cities are on the front lines of climate-driven subway flooding. And the fact that those newer systems are often better protected from flooding and fatalities underscores the urgency of adaptation.

Fabian Fuchs/picture alliance via Getty Images

“There’s a lot to learn from Asian cities, ways to deal with flooding of underground trains,” Djordjevic says. For example, in Taipei, where flooding from cyclones is common, Taiwanese authorities raised the entrances to stations to keep water out. In Kyoto, Japan, researchers built a full-scale model of a subway station escalator and simulated a flash flood to see how much water people could safely walk through and to help create emergency plans for closing stations during storms. Bangkok has long had a flood warning system to keep passengers safe, although the city has struggled to prevent underground train flooding.

Many subway systems in Asia were also built more recently than their counterparts in the U.S. and Europe, so they are better-suited to the current climate, Djordjevic says.

In the U.S., larger cities are generally doing a better job adapting to and preparing for transit flooding than smaller ones because they have more resources, Hodges says. For example, large transit departments increasingly employ resilience experts who work full time on adaptation and can also collaborate with climate scientists and engineers to come up with solutions that protect trains and passengers from flooding. Smaller cities are less likely to have such resources.

“There are definitely barriers to adapting to climate change, one of which is that it’s just difficult to interpret the information that comes in from climate scientists into actionable information that planners and engineers can use,” Hodges says.

Commuters head into New York’s Third Avenue-149th Street subway station on Thursday. Heavy rain from remnants of Hurricane Ida flooded much of the city’s subway system. Authorities issued a travel ban and warned residents to avoid stations.David Dee Delgado/Getty Images

Despite flood risk, new train tunnels are still an attractive option

The benefits of underground trains still outweigh the costs for many cities. Since Hurricane Sandy, New York has pressed forward with subway line expansions. San Francisco is expanding its subway, even as the system faces flooding from sea level rise.

Fort Lauderdale, Fla., one of the most flood-prone places in the country, is considering a new underground train line that would reduce car traffic and allow residents to commute into the downtown area by train.

Investing in new underground infrastructure in a city known as the “Venice of America” has raised some eyebrows. The editorial board of the city’s paper spoke out against the plan and argued that the train should cross a major river in the city via a bridge, rather than a tunnel.

But while Mayor Dean Trantalis acknowledges that climate-driven flooding is a worry in his city, he dismisses concerns about train tunnel flooding. “If you put in the proper pump stations and the proper technology to anticipate heavy rainfalls and things like that — I’ve lived in Fort Lauderdale for almost 40 years, and I’ve never once seen our tunnel flooded,” he says. And keeping the train underground will alleviate traffic congestion caused by railroad crossings, Trantalis says.

Experts say it’s important that new infrastructure take into account the costs of maintenance and the climate of the future. Sea level rise is accelerating in many places, including Florida. If new train systems are designed to last 30 years or more, they will need to withstand dramatically higher tides as well as more frequent and severe storms.

“When it comes to coastal areas or parts of Florida, sooner or later sea level rise will lead to some areas that need to be abandoned or protected at a very, very high cost,” Djordjevic says. “So those decisions would need to be looked at very carefully.”