This year’s recipient of the Social Innovator of the Year Award, Ashraf Patel runs Pravah and ComMutiny, two organisations that work with the youth and youth leaders at the grassroots level.

Ashraf Patel’s childhood was filled with messages and stories of co-existence, peace, and tolerance. Her father, a civil engineer, and mother, a college professor, had many tales to tell their children about how they met, crossed fabricated lines of identities, and raised a loving family.

“My father was Muslim and my mother was Jain. Theirs was a beautiful love story, which we grew up hearing about,” Ashraf recalls in a conversation with The Better India. “That was my compelling force — that love is bigger than the boundaries of identities humans have created.”

Over the course of her 29-year-long career in the social sector, Ashraf has held this same message of tolerance and love close to her heart. This also forms the basis for her organisations Pravah and ComMutiny, which have worked with thousands of youths over the years to create leaders and changemakers at the very grassroots, who fight social issues, communal divide, violence, and more.

Ashraf says that she, along with co-founders Arjun Shekhar and Meenu Venkataswaran, was deeply impacted by the 1984 anti-Sikh riots. They were all only in their late teens at the time.

Beyond what divides us

Ashraf recalls being able to see houses on fire from her terrace in a south Delhi locality, stretching as far as the eye could see. At night, she would bid her father goodbye as he would head out with a hockey stick in hand. With other members of the RWA, he would stand guard outside the houses of his Sikh neighbours to protect innocent residents from violent mobs.

Alongside the fear of what could happen to her father, there was a sense of inspiration, she says. “To see him and other members of our neighbourhood take action that way, putting aside their own needs to protect others, was both scary and beautiful. It left a seed in my mind,” she notes.

This seed would germinate when, a few years later in 1992, the Babri Masjid was demolished. By this time, Ashraf and Arjun were married, and along with Meenu, were working as HR executives in a corporation, enjoying a fast-paced life and high-paying salaries.

As riots and violence engulfed the nation once again, the trio knew that they couldn’t carry on the way that they were. “It was hard to enjoy the luxuries of life when the country was so deeply divided,” Ashraf says. “We thought we had to do something to address this polarisation. It wasn’t just out there, it was among us, in our friends and peers as well.”

As HR professionals, they had the ability to try and influence change from within, with training and value-based interventions. But instead, they were met with hesitation, because “discussing political matters” was not within the company’s ambit or something that their colleagues wished to engage in.

So the friends decided to take stock of their experiences as HR executives and young people. “We wanted to work with students and the youth to reduce violence as a whole. So we started volunteering in schools on the weekends. Our first workshop was called ‘Positive Me’, later renamed ‘From Me to We’,” she says. “That was our turning point.”

Where a river meets the ocean

The aim of ‘From Me to We’ was to help students understand the relationship they shared with themselves, and how the occurrences of the outside world can be a manifestation of what happens within. As their work gained traction and word spread across Delhi’s schools, weekends were not enough to carry on their work. They decided that at least one of them had to quit their job to be able to dedicate more time to their work.

And so, in 1993, Ashraf quit her job, and the friends formally registered their NGO, Pravah. From a workshop, ‘From Me to We’ became part of school curriculums, and teachers were involved in the movement. They set up a programme called ‘The World is My Classroom’ to encourage teachers to look at a classroom as something beyond books and a chalkboard and bring real-world experiences into their teachings.

Since its establishment, Pravah has built many programmes and collaborated with international organisations, including the UN, to encourage children to understand democratic leadership, gender inequalities, caste-based discrimination, rural development, differences of opinions and thoughts, and more. They also run programmes to support early-stage social entrepreneurs.

With this, Pravah has helped build over 7 lakh adolescent and youth leaders, and over 1,000 partner organisations. Of these, thousands have gone on to engage in various issues and sectors themselves. For example, Mohammad Aamir, who was forced into child labour after his father’s death, now teaches underprivileged children in a school he has built. Meanwhile, Esther Laltleipuii is helping Mizoram’s youth fight the trauma of substance and psychological abuse. Likewise, there are lakhs of other inspiring stories to tell, about young people who have learned from their experiences at Pravah and gone on to make significant changes in their own spaces.

“With this, Pravah aims to take a person from ‘self’ to ‘society’. We call these ‘learning journeys’ rather than training,” Ashraf explains. “We think of it as the flow of a young person’s life, like a river, which finally meets the ocean.”

To further these learning journeys, Ashraf, Arjun and Meenu also set up ComMutiny, a youth collective in 2008. This was to bring in these young leaders together under the ambit of ‘the 5th space’.

Ashraf explains, “You can say that typically, young people occupy four spaces — family, friends, education/careers, and recreation. The idea is they might not always have full agency to take decisions in all four spaces. They could be governed by factors like family decisions, rules, media influence etc. The fifth space, thus, is where young people discover themselves by engaging in social action, active citizenship, volunteering and much more. We argue that the 5th space must be re-positioned as one that focuses as much on self-transformation as it does on transforming society through youth.”

Under the ambit of ComMutiny, Ashraf also started the vartaLeap coalition. This coalition now has 120 members from 67 organisations that are engaged in various sectors and promote shared principles and values in youth work. Alongside, it offers a space for vartaLabs or co-creation spaces for new programme designs, policy frameworks. The message of this initiative is “every youth a jagrik, and every space nurturing jagriks”.

Ashraf says, “A ‘jagrik’ is a ‘self-awakened citizen, someone who is continuously learning and evolving while making social changes. It invokes internal as well as external transformation.”

For this, ComMutiny’s collective members involved youth leaders from across seven states to play Samvidhan Live, a game where one chooses a social action and self-action task, which are based on values in the Constitution of India. Through this, they aim to understand their fundamental rights and duties, and how they can execute these at individual and community levels. This session takes place every week, and they group together to reflect and discuss their learnings.

‘Every institution must join hands’

Ashraf says that youth must be viewed as beyond a group that exists to solve tomorrow’s problems.

“The lens through which institutions look at the youth must change. Investing in this group is integral for nation-building, beyond them being ‘leaders of tomorrow’. Moreover, we need bigger partnerships between governments, media, civil societies and corporations to understand the youth’s right, to give them the space to say what their own needs are,” she opines. “We need every sector to create a safe space. For this, we need to look at youth budgeting, infrastructure beyond the classroom, seed funding leadership beyond business entrepreneurship, and young people in prominent leadership positions.”

Ashraf highlights this year’s Oxfam India’s ‘Inequality Kills’ report, which stated that the “top 10 people in India hold 57 per cent of the wealth. On the other hand, the share of the bottom half is 13 per cent.” “Many issues we see today are rooted in these inequalities. Inequality, conflict — ideological, identity, and more — and deteriorating ecology are paralysing us. Leadership, more importantly, co-leadership, is the way out. It’s not just young people. All institutions need to be involved to break out of this mess.”

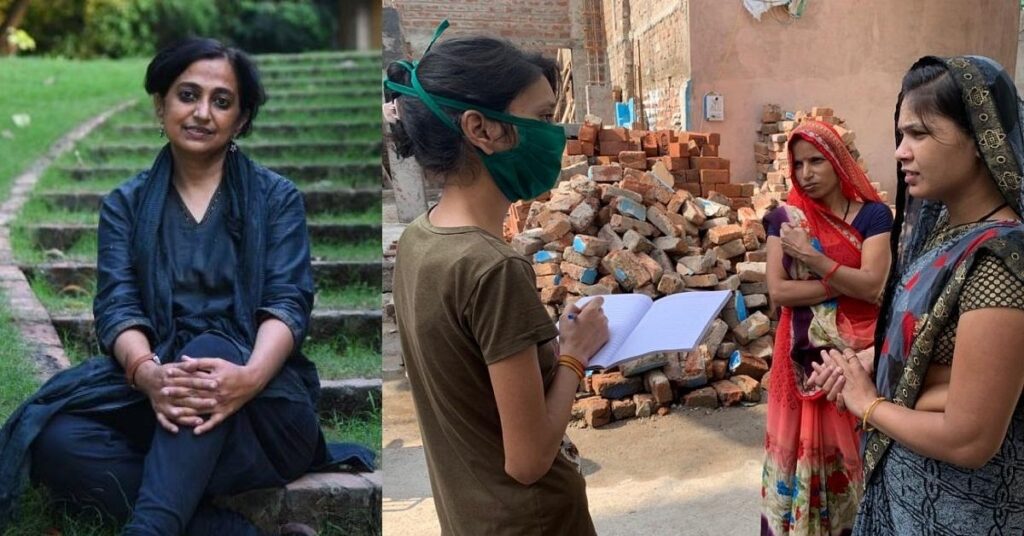

vartaLeap/ComMutiny members

“When you’re young, you have great ambition. Five years into starting Pravah, we thought we would change the entire CBSE curriculum. But now we realise that the path keeps evolving and changing. The whole system requires many different interventions. It doesn’t happen in a vacuum,” she adds.

“The recurrence of these polarising events is, in part, because we fail to acknowledge this and create a space for ideological differences to co-exist. There’s no discourse or dialogue, we don’t even talk to each other. But I have seen that when you bring people from two ends of a spectrum together, they slowly begin to see beyond their own perspectives. It’s very important to recognise these huge differences in the first place if we want to bridge these gaps,” she notes.

This year, Ashraf became the only Indian recipient of the Social Innovator of the Year Award 2022, chosen from across 190 countries and among 15 leaders. She has also been an Ashoka fellow since ‘94.

“I have learned that this will be a lifelong journey for me,” Ashraf says of her learnings so far. “Organisations are just one part of the system. It’s a vision for humanity coming together, to create a space for youth leadership to flourish. This is an evolving journey, where I’m discovering many things about myself even now.”

Article Credits: The Better India