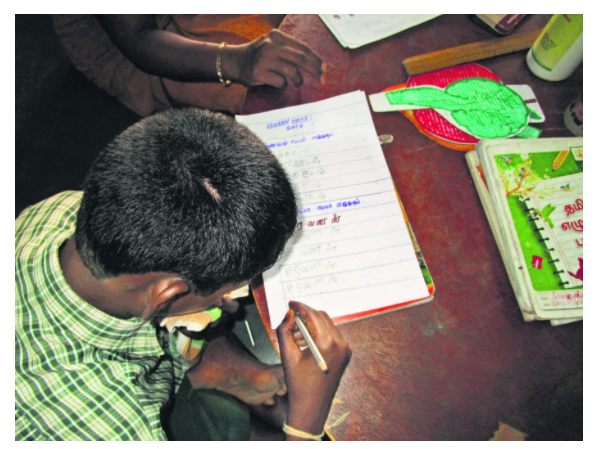

Kids at the school are encouraged to play, dance, do yoga and also taught some vocational skills | Pic: Selvarani Rajaratnam

We speak to Selvarani Rajaratnam, founder of Sri Selliah Memorial Special School for Intellectually Disabled Children about how she dedicated her life to the cause.

Every day, a few vehicles run through forty villages in Tiruchirappalli to pick up children to come to school. Come what may, these vehicles never fail to ferry these children from their village homes to the Sri Selliah Memorial Special School for Intellectually Disabled Children in the Thuraiyur block for their daily classes. Founded by Selvarani Rajaratnam, the school specialises in empowering intellectually diff-abled people from small villages, especially children of daily wagers, who are not able to afford special education for them. And they do so free of cost, under the aegis of the Sri Selliah Memorial Trust.

The story of how the Trust began is quite interesting. “We began by conducting census in villages in collaboration with NABARD. I would often go to several villages for this purpose,” says Selvarani. It was a rather ghastly incident that prompted Selvarani to start the school, though. While traversing through one of these villages, Selvarani had come across a differently-abled girl tied to a pole. “Her parents were daily wagers, who had gone to work and couldn’t leave her to loiter around the village. She was 16 years old and had urinated. Her skirt was hiked up to her waist. She didn’t know what to do. That changed me,” says Selvarani.

Children in villages, especially the differently-abled, don’t have access to the same facilities as children in cities. “Neither can the parents afford an education at such schools,” says Selvarani. “Parents in cities can also afford to drop off their children at these schools on a daily basis, but that daily wagers won’t be able to do so. If they spend time dropping and picking up their children then they won’t make it to their jobs. Therefore, most of these children are locked up in their homes or tied up when their parents leave. It was this fact that led me to start the school,” explains Selvarani.

What the kids learn

She narrates the incident of another boy, whom she also found during one of her visits. “This boy was running around the village with just his shirt on. He was not wearing any pants. When he came to the school, we taught him how to wear pants among various other things,” says Selvarani. Indeed, it is these basic life skills that the school wants to impart to its 31 students. “Other than basic skills like wearing clothes, brushing their teeth, taking a bath and so on, we also strive to impart some vocational skills to these children,” informs Selvarani. The children, who are aged between 5 and 18, are taught skills like making garlands and greeting cards. The school also teaches them dance, sports and yoga.

Other than providing special kids with an education, which also includes using sign language, identifying and matching colours and so on, the school also provides extensive physiotherapy. “A couple of years ago, a boy named Sabari joined the school. He could not walk and would only crawl. With the help of our physiotherapist, Sabari can now not only walk but also ride a bicycle,” says Selvarani. And Sabari isn’t the only one, children above the age of 18, who have passed out from school have gone into farming and other jobs in their villages. Over the years, the school has successfully trained around 50 differently-abled children.

In her initiative, Selvarani has received some support from the government too. “We have been provided with two special educations and one physiotherapist at the school,” she says. “The rest of the staff, including drivers, teachers and caretakers, are employed by the trust,” adds Selvarani. “I wanted the children to be happy and to come to school no matter what,” she says. But Selvarani is very particular that she doesn’t want to run a boarding school. “I don’t want the children to be away from their parents. Being with their parents and siblings is also a part of their growth and development. The parents should also have to assume responsibility for their special children,” explains Selvarani.

While initially, Selvarani depended on funding from her friends and relatives too, it was after the pandemic that she realised that it wasn’t sufficient. To ensure that she doesn’t face any funding issues, Selvarani has now started a crowdfunding page on Milaap as well. “I want to raise a large corpus amount and deposit it in the bank and use the interest to fund the school,” she says.

Reforming the trust

The Sri Selliah Memorial Trust, which was founded in 1993 by Selvarani’s sister, in the memory of Selvarani’s father was initially located in Nilgiris. It was in 2006 that Selvarani took over the reins and reconstituted the trust to Tiruchirappalli. “From 2006 to 2009, we were also running self-help groups to help empower rural women,” recalls Selvarani. The fateful incident with the village girl occurred in 2009, shortly after which Selvarani opened the school.

Selvarani, who now runs the trust alongside her sister, says they received their spirit of service from their father. “He worked at the International Labour Organization and helped rural people all his life. After his retirement, he settled down in Tiruchirappalli, where the trust is now located. Although it is in his memory, it is a charitable trust and not run by the family,” says Selvarani. The trust is completely run by women. Other than Selvarani and her sister, there are three other members.

Prior to working full-time for the trust, Selvarani was a lawyer. “We lived in Saudi Arabia for a while and after my husband passed away, I decided to move back. I practised law for a couple of years but never got the satisfaction. It was only then I realised that I wanted to help people in any way I can,” says Selvarani.

Article Credit: edexlive