CHENNAI: More than 30 years ago, in a tiny village in Tamil Nadu’s Kancheepuram, a bunch of 10-year-olds decided to make a new evening game out of renaming the streets — from their caste-demarcated ones to those inspired from their favourite icons. Thiruvalluvar offered L R Shankar, Ambedkar said Manivanan, and M Kannan and Gnanasekaran suggested MGR.

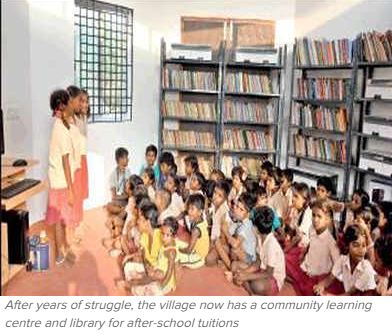

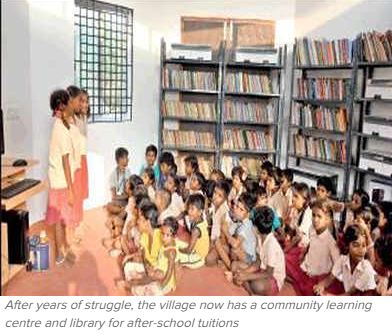

Down the years, as their adolescence gave them the insight to reflect on their own revolutionary streaks, the boys went on to create and become forerunners of Netaji Welfare Movement (NWM), an undertaking that has turned the fate of Lattur — from a failing, alcohol-afflicted village, to a citizen-driven model community. The latest milestone in their struggle is a new community learning centre and library, where village kids gather every evening for after-school tuitions and night classes, learn computers and play games. The centre has been funded by ZRII Trust, as part of the Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) of Star Life. The trust impressed by the transformation brought about by Lattur’s citizen advocacy movement, decided to back it with the necessary finances. They have also helped build the village three public toilets, which are the only such facilities in the area.

“It took us 27 years to get the names of those streets changed, by appealing to the collector. They are now collectively called Netaji Nagar,” says Shankar, the first boy in the village to have passed Class X and who went on to become a photographer. He has been active in involving everyone from the superintendent of police, local MLAs and the collector to push for changes on the ground. Similar persistent efforts over the years has meant the village now has concrete roads and drinking water facility for every household.

But one of their most remarkable achievements has been the eradication of arrack production and consumption that had crippled its menfolk and young boys for decades. Boys as young as 13 were addicted to arrack and the NWM had to battle against a powerful liquor mafia to bring them back. “It led us to face violent resistance and threats, but once the women got down to business, they feared nothing,” says Gnanasekaran. To achieve this the group’s youth approached the women in the village and carried out an obstinate door-to-door campaign.

Gnanasekaran, who went on to become president of the movement, recalls furious episodes of the women coming together to set arrack containers and brewing centres ablaze, and sitting for hours on the street demanding their complete closure. “Thanks to their exemplary revolutionary skills, every child in the village goes to school now. We’ve produced graduates too. Now that we have seen the potential of our women, our next big agenda is to form self-help groups for training vocational skills and make them financially independent.”

Article Source: Times of India