Some think it gives investors an edge, but critics point to poor results.

Socially responsible investing has come a long way from the days when it mostly meant not buying the shares of companies in controversial industries such as tobacco, firearms, alcohol or gambling.

Now, investors who favor this approach routinely consider a broad range of corporate behavior under the umbrella of so-called ESG factors—environmental, social and governance, as in corporate governance.

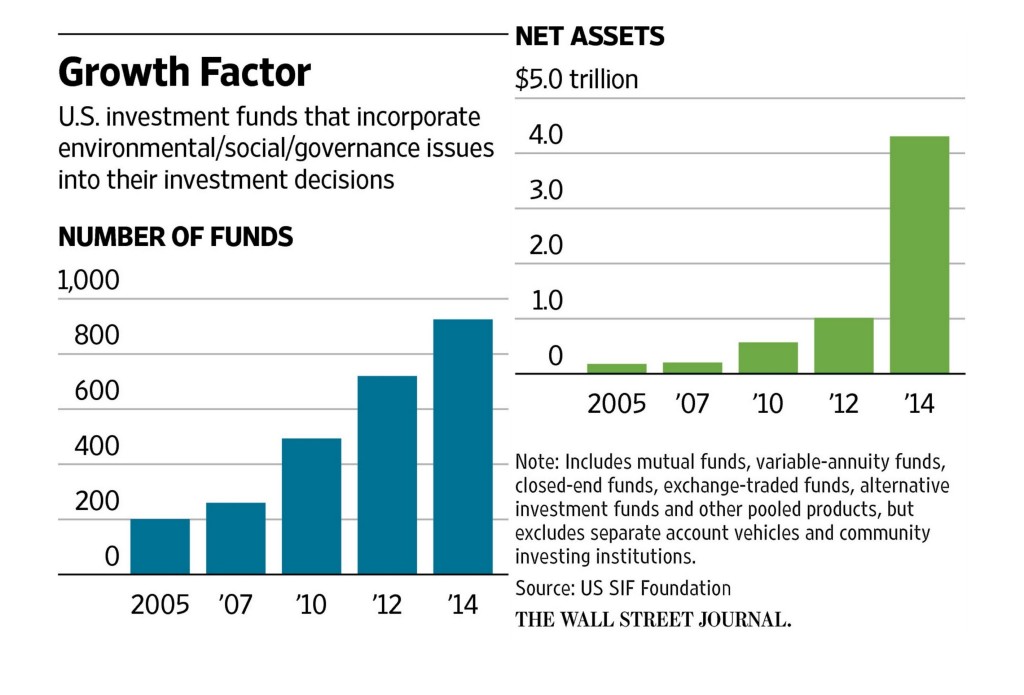

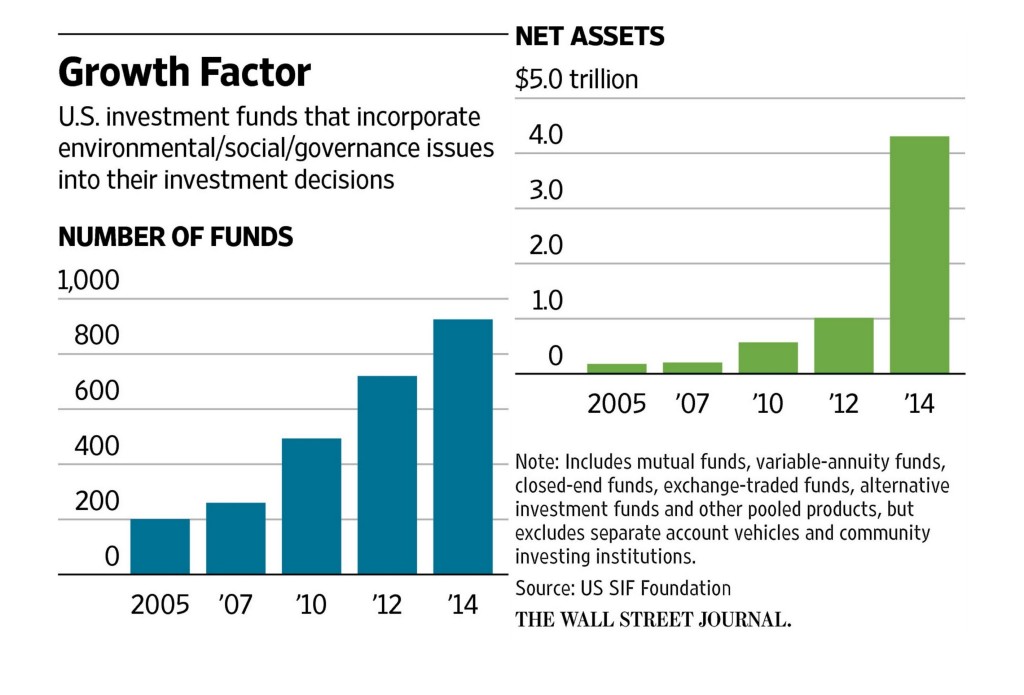

For many investors, socially responsible investing is now a guiding principle. The number of mutual funds and exchange-traded funds catering to those investors has mushroomed in recent years, with industry heavyweights BlackRock Inc. and Goldman Sachs Group Inc. prominent among those launching funds last year.

Something else has changed, as well: Investors now expect a competitive return for investing with a conscience. Some have gotten just that; others haven’t. So amid the rising popularity of ESG investing, the question of whether it pays remains.

Alex Edmans, a professor of finance at London Business School, argues that it does.

David J. Vogel, a professor at the Haas School of Business, counters that in most cases it doesn’t.

Yes: The evidence is clear that investors undervalue socially responsible firms ~~ Alex Edmans

Socially responsible investing makes financial sense precisely because many investors incorrectly think that it doesn’t—and so they undervalue socially responsible companies. That means bargains are available for astute investors.

Traditional investing focuses on tangible measures of a company’s value, such as profits and sales growth. But those measures are easy for anyone to see and understand, and so they’re already reflected in the stock price.

In contrast, social responsibility is intangible, and so investors have a particularly hard time valuing it. How do you measure the value of a company’s environmental stewardship? As a result, traditional investors mostly ignore companies’ social responsibility. They only catch on when its effects show up on the bottom line, for everyone to see. But then it’s too late—the stock price has already risen.

Years ahead

Where’s the evidence that socially responsibility pays for investors?

Let’s look at the findings of academic studies of four common social-responsibility factors. Returns for companies with high scores on the American Customer Satisfaction Index were double those of the Dow Jones Industrial Average from 1997 to 2003. Turning to governance, studies found that firms with greater shareholder rights and firms where the chief executive holds a large stake outperformed, and those that use corporate jets underperformed. Moving to the environment, companies with high eco-efficiency—that generate the least waste relative to the value of their products and services—outperformed.

Finally, on employee satisfaction, my own study shows that the returns of the 100 Best Companies to Work for in America beat their peers by 2.3 to 3.8 percentage points a year from 1984 to 2011. And although the list is public, it takes the market four to five years to incorporate it into stock prices—because this information is ignored by most investors.

A look at specific market sectors provides further evidence of the financial value of socially responsible investing. Ethical investors typically overweight health care (based on the social benefits of treating disease) and technology (because e-commerce uses far fewer resources than physical stores). Both sectors have far outperformed the S&P 500 over the past 10 years, while the energy sector (dominated by production from nonrenewable sources) has been flat overall and coal stocks have fallen substantially.

But is concern for customers, governance, the environment and employees really socially responsible? Isn’t this just good business sense? To a degree. The question is what comes first. Traditional firms will invest in stakeholders only if they can calculate a clear bottom-line impact of doing so. But, many benefits of social responsibility simply can’t be predicted. What’s the payoff to reducing emissions beyond the threshold that would avoid a fine? Responsible firms invest simply because they think it’s the right thing to do, without a mathematical calculation. The profits come as a byproduct, they’re not the end goal.

Legwork pays

None of this means that ethical investing is foolproof. Many socially responsible funds underperform their peers. But so do many traditional mutual funds, and that doesn’t mean traditional investing strategies don’t make financial sense. The crux is to evaluate socially responsible strategies, not socially responsible funds, because even ethical funds use criteria other than pure social responsibility. The shortcomings of any number of socially responsible mutual funds or companies don’t alter the premise proved by broad-based research: Ethical investing works.

It isn’t easy, but it’s getting easier. Investors don’t have to rely solely on companies to report their own socially responsible activities. Independent information like the Best Companies list or the American Customer Satisfaction Index is out there for investors willing to do the legwork. Most investors aren’t—and again, that’s the advantage of socially responsible investing.

Dr. Edmans is a professor of finance at London Business School.

No: It’s absurd to even try to separate responsible from irresponsible firms ~~ David J. Vogel

There are several reasons why a socially responsible investment strategy is unlikely to produce superior returns.

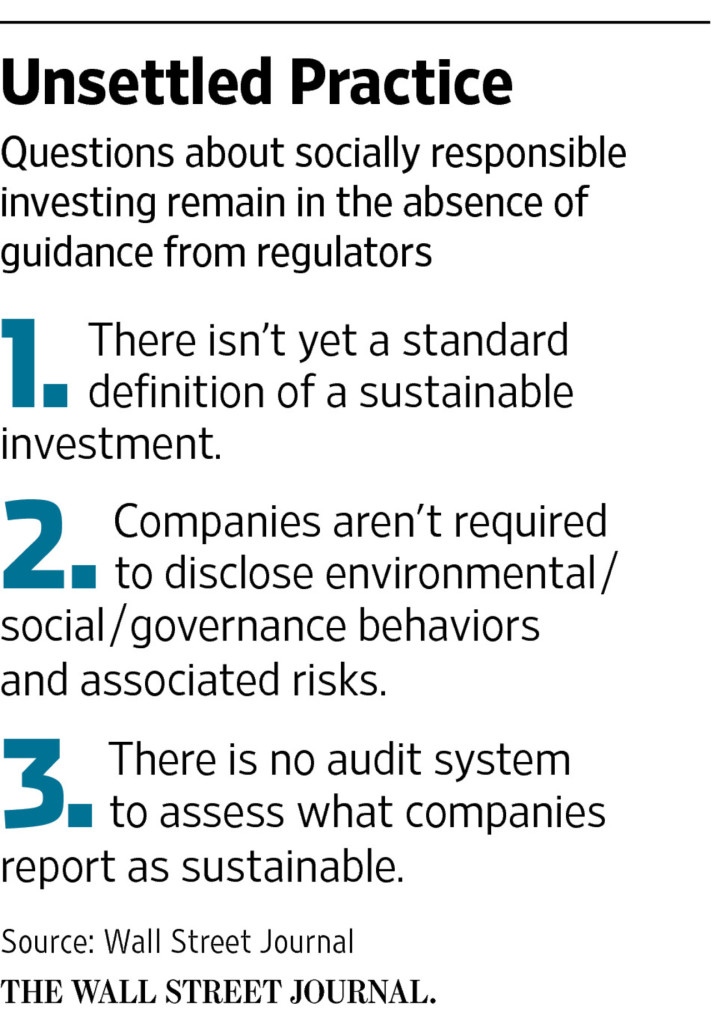

First, there is no consensus on how to define corporate social responsibility or how to construct a portfolio based on the concept. Social investment funds and socially screened portfolios employ widely diverse and often inconsistent criteria to assess both corporate responsibility and irresponsibility. How can a socially responsible investment strategy claim to produce superior returns when there is no agreement on what corporate social responsibility means or how to measure it?

Some of the strategies employed by social investment funds and socially screened portfolios have succeeded—but most have not. Over the past five and 10 years, 65% of socially screened funds have trailed the average returns of their peers.

Blind spots and complications

Second, the data used to assess a company’s social responsibility is limited and often flawed. For example, the Global Reporting Initiative, the largest voluntary reporting guideline, contains data on only 1,295 companies—less than 2% of the world’s publicly traded firms. Moreover, in the critical area of carbon emissions, analysts must rely on business self-reporting, which may not be accurate and rarely includes the carbon footprints of a firm’s products or its supply chain. These and other information gaps severely compromise the value of the criteria on which “ethical” investors typically rely.

Further complicating the picture are the mixed or ambiguous records of many companies. Does Monsanto ’s support for genetically modified agriculture make it responsible or irresponsible? Should Dow Chemical be excluded from a sustainability-screened portfolio because of past pollution or included because of its recent leadership in tracking and reducing its environmental impact and that of its products? What about a fossil-fuel company that has recently expanded its renewable-energy investment portfolio? In the real world, a company’s ethical behavior is both constantly changing and often mixed.

Third, a company’s record or reputation can be a poor predictor of its future behavior. Consider. for example, BP, Volkswagen and Chipotle —all of which had highly positive reputations for social responsibility before environmental, safety and health disasters brought down their share prices.

Missing links

Fourth, the argument that a socially responsible investment strategy “pays” assumes that paying more attention to a firm’s social responsibility—or lack of it—makes for a better predictor of future share prices. But a firm’s social-responsibility policies or practices are rarely of sufficient importance to its earnings to affect its share price. For example, while Wal-Mart ’s costs have been reduced by its many “green” initiatives, those reductions have been ignored by analysts because they aren’t material to the firm’s future earnings.

Studies that have shown a connection between certain aspects of corporate social responsibility and future share prices don’t negate studies that have shown no effect or even a negative impact from such responsibility. And any such connection shouldn’t be generalized into the superior wisdom of a socially responsible investment strategy.

As for the gains of the health-care and technology sectors in recent years, they have little to do with social responsibility—indeed, some of the behavior of many companies in both fields can hardly be called responsible.

Finally, a more responsible business strategy is no more likely to be financially successful than one that pays little or no attention to corporate social responsibility. The number of relatively responsible firms that nonetheless have suffered financial reverses is a long one and recently includes DuPont and American Apparel.

Dr. Vogel is the Solomon P. Lee emeritus professor in business ethics at the University of California, Berkeley’s Haas School of Business.

This article was taken from here.