Viewing CSR strategy through a litigation prism may, at first glance, seem cold blooded or cynical. It is neither.

Litigation readiness is a proxy to understand the rigor of a company’s approach to CSR due diligence and response. It does not mean thinking of CSR as exclusively a legal issue. And it certainly does not diminish the importance of stakeholder engagement. Rather, litigation readiness is about being able to explain to objective observers how a company’s CSR practices align with international standards. In other words, it is the cornerstone of effective transparency.

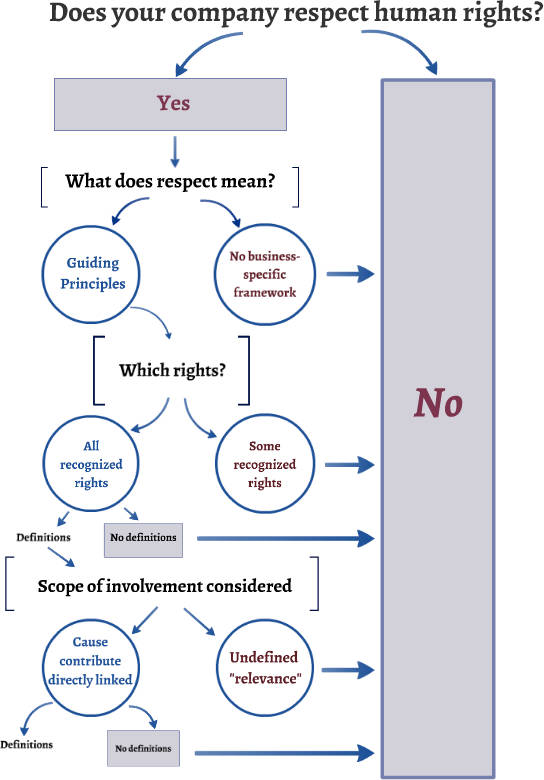

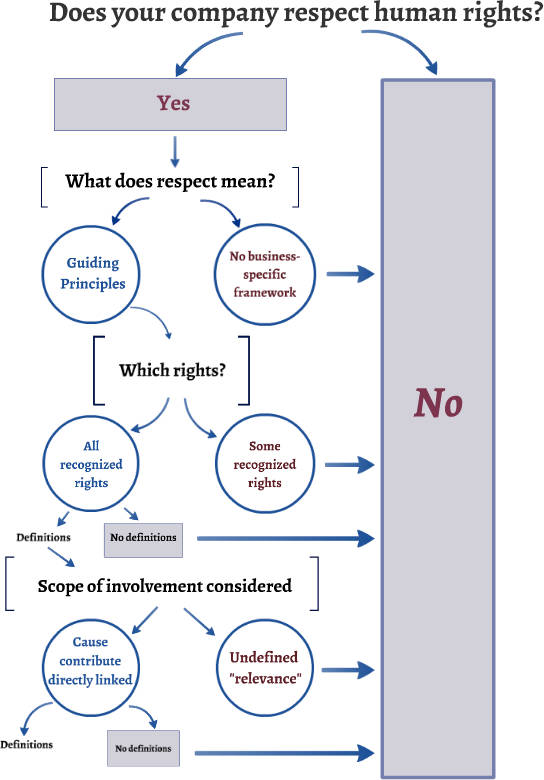

In the human rights context, litigation readiness is about a company’s ability to justify the following statement: “We respect human rights.” That statement cannot be made cavalierly, because the making of it can ground legal claims (see, e.g., Choc v. Hudbay). Following the widespread adoption of the Guiding Principles by the public and private sectors, a company’s claim to respect human rights is implicitly a claim that it has a system in place to identify, prevent or mitigate, and remediate its impacts on all internationally recognized human rights. It is this system that a company must be prepared to defend.

Responding to a hypothetical cross-examination is a good test of a corporate human rights system, for it is arguably the most exacting look at the underpinnings of the business’s approach—by a party intent on proving failure. While there are myriad questions a company may face, there are a few foundational issues that could derail a defense of the most sophisticated and well-financed corporate program.

We provide below a hypothetical series of questions that apply in any legal or quasi-legal context where a business’s human rights strategy is in issue—from the institutional investors criticized by the Norwegian NCP to mining companies being sued in Canada for transnational torts (see, e.g., Choc v. Hudbay and Garcia v. Tahoe Resources). [NB: The series of questions is necessarily a simplification for illustrative purposes.]

The flow chart above illustrates a number of threads that can be unspooled in cross-examination. While the responses will not generally be binary, they can nonetheless be broken into two broad answer types—one of which leads to a finding that the company does not respect human rights.

The text below explains how certain answers undermine a company’s claim to respect rights.

Question 1. Does your business respect human rights?

Answer 1(i). Yes.

A1(ii). No. [An unlikely response, which paves the path to liability.]

Q2. What does respect mean to you?

A2(i). We have adopted and strive to follow the Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights, which provide the most widely endorsed framework for business responsibility for human rights.

A2(ii). We have made it our mission to respect the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which is the bedrock of international human rights. [This leads to the following: The Universal Declaration makes no provision for business responsibility for rights. What framework do you use to understand or define what it means for your business to respect the rights identified in the Universal Declaration? If no framework, then the “respect” claim is immediately belied—for how can you respect rights without a definition of “respect”? If a framework other than the Guiding Principles, then subject to challenge for incompleteness or idiosyncrasy.]

Q3. Which human rights is your system designed to respect, i.e. through due diligence and response?

A3(i). All internationally recognized human rights.

A3(ii). Labor rights, health and safety, community relocation (or any other specific enumeration). [This leads to the following: So you do not respect all human rights. At the very least, you do not actually follow the Guiding Principles, the framework you claim guides your action.]

Q4. What definitions do you use to understand the meaning of rights?

A4(i). We rely on the commentary of relevant UN committees, the jurisprudence of international courts, and domestic commentary and jurisprudence relevant to the jurisdiction in which we operate.

A4(ii). We do not have particular definitions. We refer to the text of the Universal Declaration and the ILO Core Conventions. [This leads to the following: These instruments do not give any guidance regarding what a right means in any particular context. So, if you are not referring to more detailed commentary, your decision regarding whether any given operation affects human rights is based on conjecture.]

Q5. How do you determine the scope of relevant involvement with rights impacts?

A5(i). In accordance with the Guiding Principles, we determine whether we are involved with any adverse human rights impact with reference to whether we cause or contribute to that impact and whether we are directly linked to that impact through our business relationships, even if we have not caused the impact ourselves.

A5(ii). We consider “relevant” impacts based on our operations and stakeholder concerns. [This leads to the following: So your approach is ad hoc, not systematic. It is based on perception rather than involvement. Moreover, it means you do not actually follow the Guiding Principles, as you claim.]

Q6. How do you define “cause and contribute to” and “directly linked to”?

A6(i). Relying on relevant expertise, we have developed reasonable internal definitions of “cause and contribute to” and “directly linked to”. These definitions inform the scope of our due diligence, so that it is consistent and comprehensive.

A6(ii). We do not have definitions. We know what these terms mean. [This leads to the following: Do you cause an adverse human rights impact if the impact would not have happened but for your operations? Does it matter if you could foresee the impact? Do you consider yourselves directly linked to human rights abuses by all governments with which you have a business relationship? If no, why? If yes, what do you do in response? This series of questions, including potential hypotheticals involving the company itself, will be almost impossible to respond to without a definition.]

Preparing for cross-examination ensures rigorous due diligence

This is, of course, a simplified illustration of a potential cross-examination. The objective is to highlight vulnerabilities that exist at the first layer of questioning if a company has not properly thought through its CSR strategy. The next series of questions would test whether the definitions are actually used in practice.

And these questions are relevant not only for potential litigation, but for transparency more generally. How a company understands human rights and the scope of its responsibility turns on the definitions it uses, if any. This rigor is a mark of a corporate commitment to respect human rights that can and should inform sustainable investment decisions, lending due diligence, mergers and acquisitions, and stakeholder perception more generally.

Litigation readiness is not about revolutionizing CSR strategy or taking the human element out of it. Rather, it is about developing a back office operation to ensure the efficacy of the diligence and response systems. The back office does not usurp traditional CSR functions like stakeholder engagement—it supplements and informs them. It provides an underlying structure to the act of due diligence to ensure that it is looking for the right information, and is, therefore, defensible.

This article was taken from here.