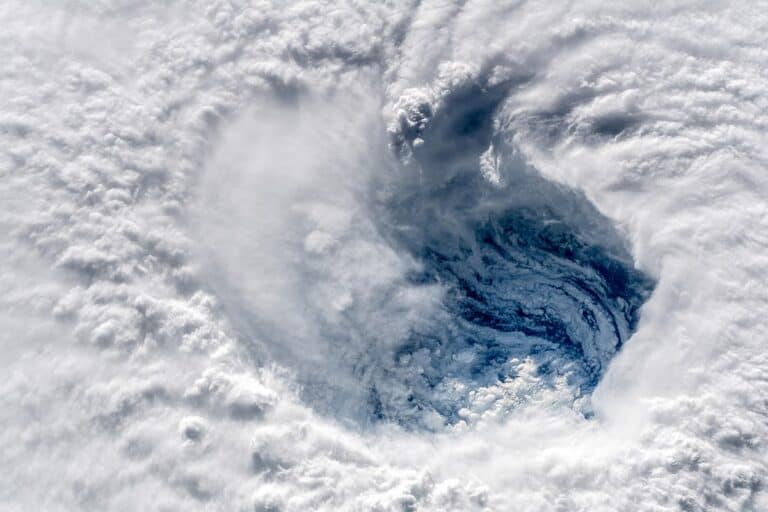

Hurricane season in the Atlantic has been particularly bad this year, “pushing the limits of what meteorologists thought was possible,” CBS News succinctly put it.

The Atlantic hurricane season, which officially concludes at the end of this month, has spawn as many as 30 tropical storms so far, six more than even the most dire forecast would have it earlier this year.

Forecasters had “to dig deep into the Greek alphabet for names, having run out of the assigned names in the middle of September,” CBS noted. “This breaks the former record set in 2005 of 28 named storms. A typical season only produces 12 named storms, so 2020 has already seen two and a half times more than average.”

Yet what may seem like an anomaly is set to become the new normal with hurricanes as a result of climate change. And not only are they going to be more hurricanes, but they are also set to become more destructive when they make landfall.

A team of scientists in Japan has found that warming weather is causing hurricanes that end up making landfall to take more time to weaken, which means they can travel farther inland, covering a larger area, and so become far more destructive to people’s lives and property.

The reason, they explain in a new study, is that hurricanes are fueled by moisture from the ocean and once they make landfall their intensity decays fast. However, warmer ocean temperatures cause this so-called hurricane decay to slow down over land, meaning that the storms can have a larger impact by reaching farther inland than before.

In fact, over the past half century hurricane decay has slowed down in direct proportion to a rise in sea surface temperatures, the scientists found. “[W]hereas in the late 1960s a typical hurricane lost about 75 per cent of its intensity in the first day past landfall, now the corresponding decay is only about 50 per cent,” they write.

This has grave implications for inland communities along hurricane-battered shorelines that have so far been spared the worst ravages of the storms, says Professor Pinaki Chakraborty, a senior author of the study who is head of the Fluid Mechanics Unit at the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology Graduate University in Japan.

“We know that coastal areas need to ready themselves for more intense hurricanes, but inland communities, who may not have the know-how or infrastructure to cope with such intense winds or heavy rainfall, also need to be prepared,” Chakraborty warns.

Other studies have already shown that warming temperatures can intensify hurricanes, which are also known as cyclones and typhoons in regions of the Atlantic such as East Asia, over the ocean. However, the new study establishes a clear link between a warming climate and those hurricanes that actually make landfall.

And changes in temperatures have a direct bearing on their intensity, explains Lin Li, an author of the study. “When we plotted the data, we could clearly see that the amount of time it took for a hurricane to weaken was increasing with the years,” the researcher says. “But it wasn’t a straight line — it was undulating — and we found that these ups and downs matched the same ups and downs seen in sea surface temperature.”

Considering the nature of hurricanes, this finding should not come as too much of a surprise.

“Hurricanes are heat engines, just like engines in cars. In car engines, fuel is combusted, and that heat energy is converted into mechanical work. For hurricanes, the moisture taken up from the surface of the ocean is the ‘fuel’ that intensifies and sustains a hurricane’s destructive power, with heat energy from the moisture converted into powerful winds,” Li explains.

“Making landfall is equivalent to stopping the fuel supply to the engine of a car. Without fuel, the car will decelerate, and without its moisture source, the hurricane will decay,” she adds.

Once a hurricane makes landfall, it no longer has access to the ocean’s supply of moisture, but it can still carry the amount of moisture it has stored, which depletes over time. “Hurricanes that develop over warmer oceans can take up and store more moisture, which sustains them for longer and prevents them from weakening as quickly,” Li says.

That is why climate change is bad news when it comes to the intensity of hurricanes. “If we don’t curb global warming, landfalling hurricanes will continue to weaken more slowly,” Chakraborty notes. “Their destruction will no longer be confined to coastal areas, causing higher levels of economic damage and costing more lives.”

Article Credit: sustainability-times