In the past few years, a varied range of non-dairy alternatives have emerged on the market. Whether it’s soy, almond, oat, coconut, hazelnut, rice, or whatever, milk alternatives have become a common sight. For many of the over 4.7 billion people who are lactose intolerant, this has been a godsend. Many prefer them to reduce the intake of animal products, while for others, it’s about reducing environmental impact.

But are milk substitutes truly more eco-friendly than the alternatives? The short answer is ‘yes’. The long answer is more complex, however. Let’s see what the science says.

What’s plant milk anyway?

Plant milk (or alternative milk, plant drink, or whatever you may call it) is an umbrella term for non-dairy beverages made from plant extracts that are somewhat similar to milk — at least in their usage. Contrary to popular belief, plant milk isn’t a new idea. The Spanish drink horchata (or orxata) was already popular 1000 years ago, and soy milk has been mentioned in historical texts since the 3rd century BC.

In very recent times, plant milk has diversified and become more common , particularly as a way for people to reduce their animal protein consumption, but also for people suffering from lactose intolerance or just wanting to have an alternative to milk. Recent consumer reports show that plant milk is growing in popularity every year, with 50% of the people in the US and Europe saying they consume it at least once in a while, either exclusively or alongside cow milk. In Britain, for instance, 1 in 4 consume plant milk almost exclusively.

Because there’s so much variety, we have to look at different types of plant milk separately — just like cow’s milk itself can have a different environmental impact based on how cows are fed. However, as we’re about to see, plant milk is virtually always more eco-friendly than cow’s milk.

Plant milk is more eco-friendly than cow’s milk

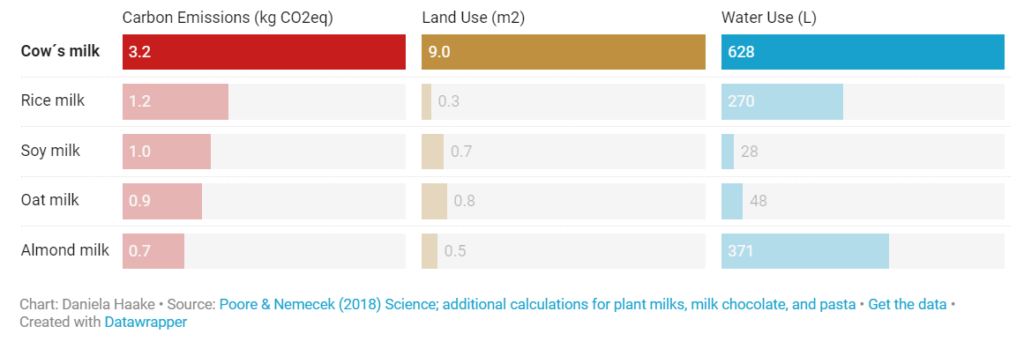

When it comes to how eco-friendly or sustainable a product is, three main things are usually in focus: emissions, land use, and water use.

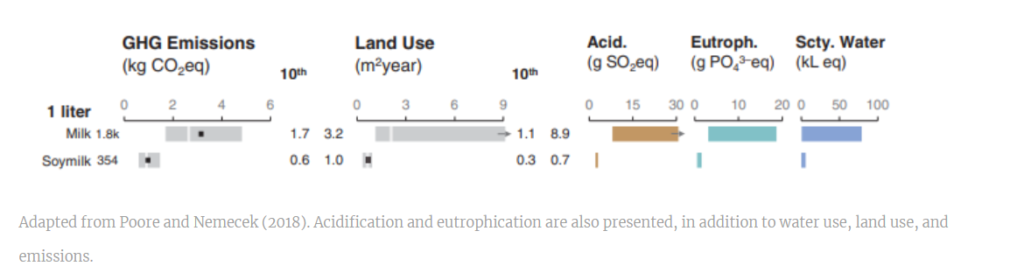

Because there’s so much variability involved, studies can come up with different values which is why, if you want to understand the big picture, you need to look at multiple studies. A University of Oxford study did just that: they analyzed global averages for multiple types of foods, looking not only at the median values but also at the ranges of emissions, land, and water use. In all instances, all analyzed types of plant milk (rice, soy, almond, oat) behaved better than dairy milk.

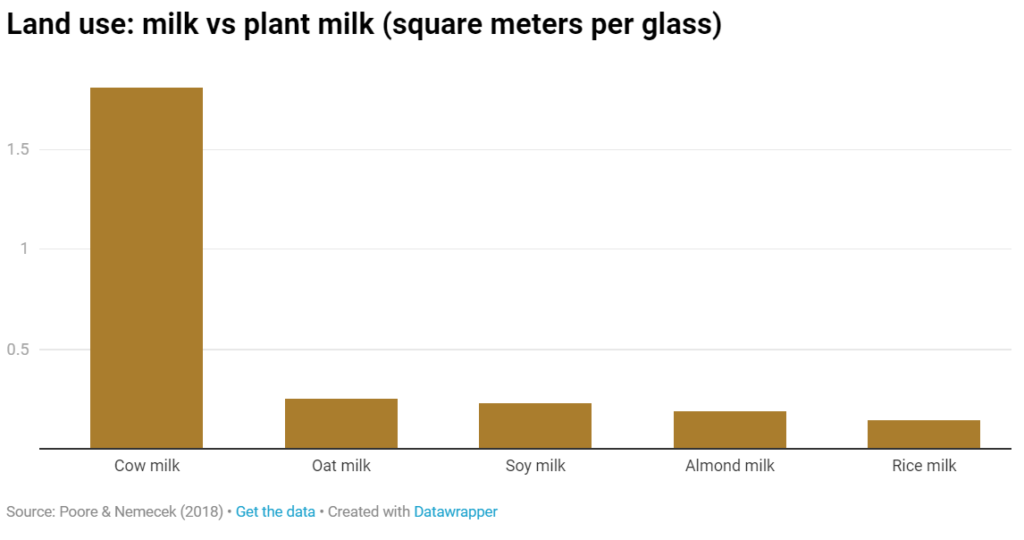

Drinking one glass of dairy milk every day for a year would require 650 sq m (7,000 sq ft) of land — the equivalent of two tennis courts. Oat milk, by comparison, requires 10 times less. Soy, almond, and rice fare even better in this regard. Emissions wise, all the plant milk fared about 3 times better than dairy milk. Water use is where there were the biggest differences, with almond milk being the thirstiest of the non-dairy bunch, but still way below what cow’s milk requires.

“Most strikingly, impacts of the lowest-impact animal products typically exceed those of vegetable substitutes, providing new evidence for the importance of dietary change,” the researchers conclude.

Food production is responsible for a quarter of all human-produced greenhouse gas emissions and, calorie for calorie, animal products are generally the main culprits. While milk is not as big a problem as meat, it’s still an important contributor to our emissions.

Almond milk is the most problematic in this category, especially as almonds are usually grown in drought-prone areas such as California, Spain, and Italy. Rice is also demanding, requiring over 50 liters of water per glass, while soy and oat can do with far less.

Land use: milk vs plant milk (square meters per glass)

Almond milk is the thirstiest of the bunch, especially as almonds are usually grown in droughty areas such as California, Spain, and Italy. Rice is also demanding, requiring over 50 liters of water per glass, while soy and oat can do with far less.

Milk has higher environmental impact than vegan substitutes

This is where the differences get more striking — no alternative comes even close to cow’s milk.

It’s worth noting that even when we look at the full range of situations, the study found virtually no scenario where cow’s milk is more sustainable. While there could be localized exceptions, in general, plant milk used fewer resources across the entire range of scenarios.

So which one is the most sustainable?

All non-dairy kinds of milk are much better for the environment than cow’s milk. They all use less land, water, and generate lower emissions. The main reason for this is cows: as inefficient as the production of plant milk may be, living organisms are even more inefficient. Cows require a lot of land and water, and they produce a lot of emissions, including methane, which is a much more potent greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide.

If you’re interested in picking the most eco-friendly option, it all depends on what you prioritize. If you’re most interested in reducing emissions, almond is best, but it consumes a lot of water. Rice seems to be the overall least eco-friendly, while soy is a good all-around option (we’ll see in a moment, it’s also the healthiest). Oat is another safe option, also because it’s often grown in cooler climates like North America, where deforestation is not as severe as in developing countries.

The discussion about which one would be best can get very complex, but ultimately, all types of plant milk are much better for the environment than dairy.

What about the other ones, like coconut?

Not all types of plant milk are presented in the study above, just the most common ones. It’s worth noting that there are other alternatives (like the above-mentioned horchata, coconut, or hazelnut, for instance). Because they are less popular, there are also fewer studies, but here’s what we know.

Coconut milk is not a particularly environmentally-friendly option and contrary to popular belief, it’s also not very nutritious. Horchata is mostly a local specialty. Pea milk can be a sustainable alternative, particularly as it’s rich in protein but it’s not very common, while hazelnuts are one of the most eco-friendly tree nuts, tolerating poor soils. There are plenty of other alternatives, both with their pros and cons.

In general, however, all these fare better than dairy milk in the above-mentioned categories.

But wait, I read an article that said differently

There are a couple of things to be said here. As mentioned, there is great variability in how different types of milk (both dairy and non-dairy) are produced. A glass of milk in New York can be very different from a glass of milk in Singapore. However, while there may be exceptions, this difference is still not generally enough to make dairy milk a more sustainable alternative.

However, plant milk is not devoid of blame. Emissions, land use, and water use, are the biggest environmental metrics, but they’re not the only ones. Oat, for instance, is usually grown in monoculture, which can be associated with a higher use of pesticides and lower biodiversity. Almonds are reliant on pollination by bees, which can be taxing for the pollinators, and coconut extraction has sometimes been linked to worker abuse.

Meanwhile, cows can be fed on sustainable natural pastures where nothing else is grown, so there can be situations when dairy milk is more eco-friendly — but these are generally rare, and even where dairy milk fares best, it’s usually only by comparison with the worst of the plant milk. For soy, the main environmental drawback is that it is grown in massive quantities around the world to feed livestock for meat and dairy production — but if the demand for milk is reduced, the demand for soy will also be reduced.

You may be fooled into thinking that buying local milk is more eco-friendly than alternatives that come from far away — but transportation usually constitutes a very small part of the product’s total emissions.

Barring some niche situations, alternatives like soy, oat, or hazelnuts are better environmental options than dairy, but the conversation is not always simple and straightforward.

What about the nutritional value?

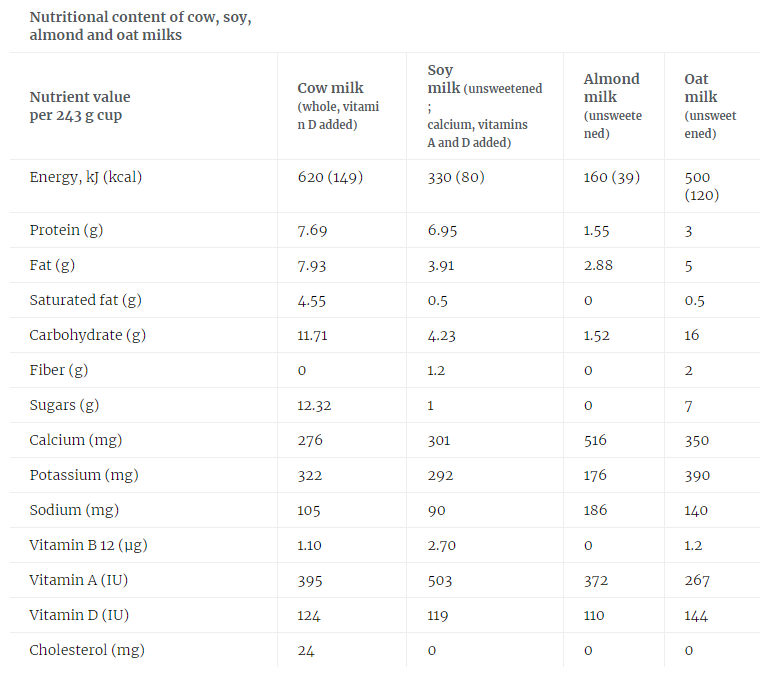

You’ll notice that the comparisons above are per glass. Critics of plant milk love to point out that plant milk is not as nutritious as cow milk, but that’s not really the case. Pound per pound, cow milk has more calories than plant alternatives, but that’s not necessarily a good thing.

Nutrition-wise, studies suggest that soy milk is the most nutritious of the plant options. It has approximately 2 times fewer calories than dairy, just as much protein, and far less saturated fats and sugars — and no cholesterol. Here’s how plant and cow milk compare nutritionally:

There are advantages and disadvantages. If you’re afraid of cholesterol and sugar, cow milk might not be the best thing. If you like protein, cow and soy are very similar, and if you’re after calcium, almond (or again, soy) might be better options.

The bottom line: as long as it’s not dairy

When it comes to nutrition and the environment, things are rarely simple and straightforward — this is no exception.

No matter how you look at things, however, dairy milk seems far less environmentally friendly on average. Animal products (including milk) make up an important part of society’s total emissions. According to Dr. Adrian Camilleri, a psychologist at the University of Technology Sydney quoted by the BBC, consumers greatly underestimate the emissions associated with milk; water and land use are not far off, either.

There is great variety between the environmental characteristics of different plant milks. Some, like soy, oat, or pea, tend to be more eco-friendly than almond, coconut, or rice, but it depends what you’re looking at, specifically.

Nutritionally, dairy milk has some advantages, but it’s hard to say it is strictly better than alternatives — it fares well in some regards, and poor in others. While it does have important nutritional value, it’s also rich in sugar and cholesterol, and protein-wise, it’s similar to soy milk. Dairy milk also has more calories per pound than regular milk — which can be considered either an advantage or disadvantage, depending on what you’re looking for in milk.

Overall though, if you’re concerned about the environment, switching to plant (or alternating between plant and dairy) is already a step in the right direction.

Article Credits: ZME Science

Pingback: World Plant Milk Day 2023: Date, History, Significance, Facts - SLSV - A global media & CSR consultancy network

Pingback: Revolutionizing plant-based meat: Indian-origin scientist-led team pioneers palatable alternatives - SLSV - A global media & CSR consultancy network