Inequality has been moving up the global agenda ever since the financial crisis of 2008, fanning the flames of of populism.

In the rich world, a majority of people feel they do not get a fair deal and social mobility has stalled in many countries, meaning children from poorer backgrounds remain disadvantaged for life. Meanwhile, analysis from the World Economic Forum shows economic growth does not necessarily translate into progress on tackling inequality.

At the World Economic Forum’s Annual Meeting in January 2019, we spoke to Minouche Shafik, director of the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE), and former Deputy Governor of the Bank of England. Below is an edited transcript.

How do you define the idea of fairness and a fair economy?

A fair economy would be one in which, if you didn’t know where you would land in that economy – you didn’t know which family you would be born into, or where you would be born – that you would think, I could have a good life in that economy.

What is unfair about the way today’s economy works?

In today’s economy, too much of what happens to you depends on which family you’re born into and the opportunities that brings. What most people would like to see would be a society and an economy in which everyone was guaranteed a minimum, so nobody would be absolutely destitute. But also that, if you worked hard and tried hard, you could advance yourself regardless of which family you were born into.

What mechanisms do we already have in place to try to ensure that the economy is fair and that people are given a fair chance?

We have two mechanisms to try and make the economy fair. We have what economists call pre-distribution policies. That means things like education and skills training and ways to help people do better, before the government gets involved in terms of spending.

And then we have post-distribution policies, which mean after you have gone to work, the government will sometimes tax you, or give you benefits to try and compensate you for any unfairness in the economy. Those are the current mechanisms we have and arguably neither of them are working sufficiently well.

What’s wrong with them, what are their biggest weaknesses?

The problems with what we call pre-distribution policies – our education systems – they don’t do enough to compensate for disadvantage early on. A lot of research now shows that it’s the first thousand days of life that matter enormously for life outcomes. So very early years education, nutrition at a very young age, interventions at that point can have huge benefits in terms of people’s major health and educational outcomes and career prospects. So we aren’t doing enough at the very beginning.

And our educational systems are still very unequal. People who are better off can hoard opportunities and keep them for their own children, through things like private schooling and private tuition. We also could do much, much more when people finish school, to support them so that, if they lose their job, they’re able to acquire new skills quite easily to find a new one.

What big changes do we need to make to achieve a fairer society?

We would need to invest much more in early years education, particularly for kids from disadvantaged backgrounds. And we would need to try and compensate for the lack of opportunities that they might have because of where they’re born. That might mean giving them opportunities to access more interesting educational experiences, be it in science, or art, or digital training.

We also would need to help support them to get into higher education, if that’s the right path for them, in terms of scholarships targeted toward disadvantaged young people. Once they finished university, we need to make sure that, as the labour market changes, they have opportunities to reskill and retool. That means a much bigger investment than we’re currently making in lifelong learning.

How can countries afford this? Is it a cost or is it an investment?

Investing in people’s skills and education is probably one of the best investments that countries can make. We know we’re going into a knowledge economy. The most important asset countries have is their people and the returns to good investment in education and skills is very, very high. So I think the affordability argument is a bit of a false premise.

The other aspect of a fair economy is redistribution. There the question often comes up: can countries afford to transfer income to the lowest income parts of society?

There is obviously an issue of justice and social cohesion, and also an issue of stability and holding a society together. If people don’t think that the way the economy is organized is fair, they will vote for political parties and politicians who promise them something different. So that too is a very important imperative for making sure that our countries are much fairer.

There is obviously an issue of justice and social cohesion, and also an issue of stability and holding a society together. If people don’t think that the way the economy is organized is fair, they will vote for political parties and politicians who promise them something different. So that too is a very important imperative for making sure that our countries are much fairer.

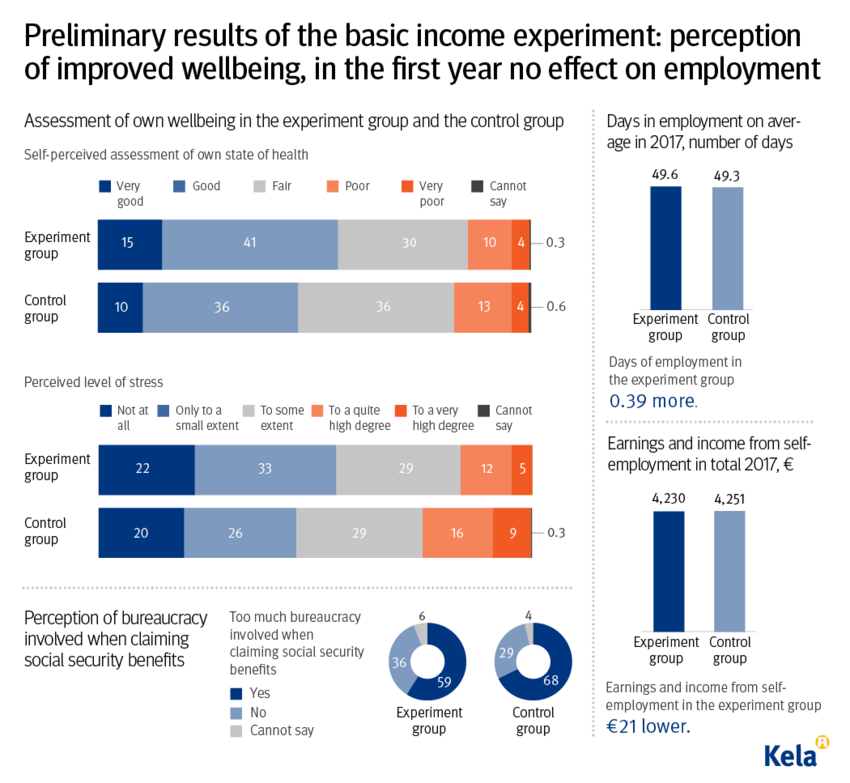

Could some form of Universal Basic Income be part of the solution for a fairer society?

Universal Basic Income is a solution in a very small number of cases, in particular in low income countries where it’s often just more efficient to distribute very small amounts of money to very poor households, and where targeting doesn’t make sense because most people are very poor.

I also think it makes sense where you’re using it to substitute for something that’s much worse and more inefficient like, if you have energy subsidies and you decide to compensate people with a fixed amount of income.

I think for any country that can manage a proper welfare state – so for most middle-income and high-income countries – I think Universal Basic Income is a very expensive policy, that will cost something like 5 or 6% of GDP, which is quite a lot of money.

You could use that money much more efficiently through things like topping up the wages of workers who are very low earners, for example; or increasing the minimum wage; to make sure that the benefit goes to those who need it the most.

So for most richer countries, I think Universal Basic Income is not the solution and there are much better solutions that would use the resources and get them to those who need them most.

What role should governments and business play in finding solutions for a fairer economy?

Everyone has a role to play in trying to make the economy fairer. Governments obviously have a huge role in the way they tax and spend, and the way they make sure that benefits go to those who need it the most, and that they provide a floor for everyone of basic levels of income, education, and healthcare. They also set the rules which govern how the private sector operates.

The private sector also has a huge role to play, in particular around the terms of their employment, and whether they provide workers with decent work and reasonable benefits, even if they’re not working full-time.

Business also has a huge role to play in social mobility. They can, if they choose, make sure that they hire people and give support to those who might be coming from disadvantaged backgrounds, who then might be able to advance enormously in their organization.

The private sector can serve as a model and an inspiration to their employees, if people feel that they are doing their bit to promote equality.

Is it the role of economists to measure a society or to change a society?

Good economists do care a lot about measurement and they shouldn’t think about measurement in a very narrow, mechanical way. Everything is not about GDP, and can’t be measured in units of money.

We’ve done quite a lot of research at the LSE on wellbeing and what makes people happy. What we find is that, up to a point, more income makes people happy. At a very early stage, when incomes are not very high, giving people more money doesn’t do much to make them happier.

In fact, what we find makes people happy is having good health – both physical and mental, good relationships, and meaningful work. Those three things are the key drivers of what makes people happy; and those are important things that economists should increasingly measure.

Economists obviously have an important role to play in helping society assess the economic consequences of changes it wants to make. Every society has to make choices: between efficiency and equity, which do you value most; what to invest in. Economists can play a really valuable role in providing society the tools and the analysis to make those very difficult choices.

Article Credit: We Forum