Results from a decades-long field study in Minnesota reveal the dangerous impact of rising carbon dioxide and nitrogen pollution on grassland biodiversity.

Though it’s well documented that nitrogen pollution decreases the richness of plant species and that rising levels of atmospheric carbon dioxide are driving climate change, scientists have been unable to determine if rising carbon dioxide levels influence plant diversity or modify the negative effect of nitrogen pollution on diversity.

Studies like this are uncommon because of how challenging it is to evaluate the impact of the gradual rise in atmospheric carbon dioxide by observing changes in vegetation and the extended time required to make the data relevant.

In the 1990s, a team of University of Minnesota researchers launched a rare experiment to address this knowledge gap. The experiment lasted for decades and their most recent findings were just published in Nature.

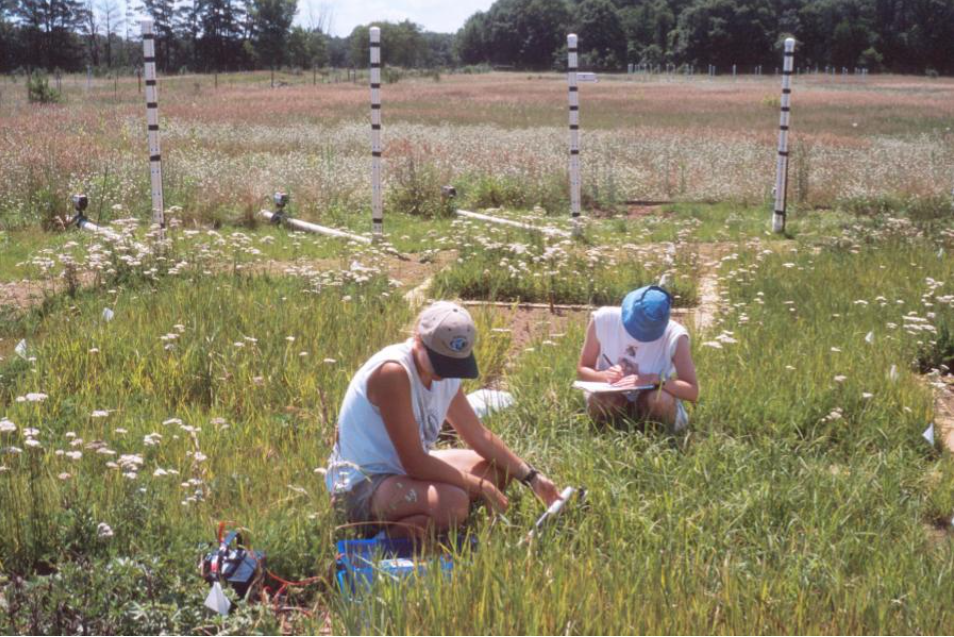

The field experiment manipulated carbon dioxide, nitrogen and plant diversity. In 1997, researchers planted perennial herbaceous species on more than 100 grassland plots at the U of M’s Cedar Creek Ecosystem Science Reserve in east central Minnesota. The plots were planted with varying levels of species diversity and were treated from 1998 to 2021 with combinations of ambient carbon dioxide and experimentally elevated carbon dioxide, and ambient and enriched nitrogen (similar to levels of nitrogen pollution that occur in many places on Earth). The researchers counted the species every year and studied the loss of species diversity in each plot as well as the mechanisms that might have driven changes resulting from carbon dioxide and nitrogen enrichment.

They found:

- The added nitrogen always reduced species diversity, but its effect worsened over time when levels of carbon dioxide were higher.

- In the first eight years, added nitrogen reduced species richness by 13% under ambient carbon dioxide and by only 5% under elevated carbon dioxide. Over time, this effect flipped.

- During the last eight years, added nitrogen reduced species richness on average by 7% under ambient carbon dioxide and by 19% under elevated carbon dioxide. In short, rising carbon dioxide nearly tripled the losses caused by enriched nitrogen during that later period.

“If rising carbon dioxide generally makes the negative impacts of nitrogen deposition on plant diversity even worse, as observed in our study, this bodes poorly for conservation of grassland biodiversity worldwide,” said Peter Reich, the study’s lead author and a research professor at the University of Minnesota’s College of Food, Agricultural and Natural Resource Sciences.

The processes that drove large diversity losses mostly involved increased light competition and are likely to occur in grasslands around the world. That is because higher levels of carbon dioxide and nitrogen (from fossil fuel emissions and nitrogen pollution, respectively) will likely favor the abundance of dominant species and create shadier conditions beneath them, stymying the growth of other species. However, whether these effects occur in other biomes on the planet is a mystery because of the lack of useful experimental or observational studies.

The co-authors of this study include Neha Mohanbabu, a postdoctoral researcher in the College of Food, Agricultural and Natural Resource Sciences; Forest Isbell, an associate professor in the College of Biological Sciences; Sarah Hobbie, a professor in the College of Biological Sciences; and Ethan Butler, a research associate in the College of Food, Agricultural and Natural Resource Sciences. This long-term research was also aided by more than 200 undergraduates, some of whom helped each summer over the nearly quarter century of the project.

“This study simply would not have been possible without the hard work of the teams of students who measured the plants and soils, often in challenging field conditions, so we could develop a truly long-term experimental record,” said Hobbie.

This research was supported by the National Science Foundation.

Article Credit: twin-cities