Glacial melting due to global warming has probably been altering Earth’s poles since at least the 1990s, a new research said.

The axis Earth spins around is always moving and the way water is distributed on Earth’s surface is one factor that drives the drift. Melting glaciers redistributed enough water to cause the direction of polar wander to turn and accelerate eastward during the mid-1990s, according to a new study published in Geophysical Research Letters.

The melting of the world’s glaciers has nearly doubled in speed over the past 20 years, according to a comprehensive new study published in Nature.

Between 2000 and 2019, glaciers lost 267 gigatonnes (Gt) of ice per year, which now account for about a fifth of global sea-level rise. The authors estimated that the mass loss was equivalent to submerging the surface of England under 2 metres of water every year.

Notably, half the world’s glacial loss is coming from the United States and Canada, the study found.

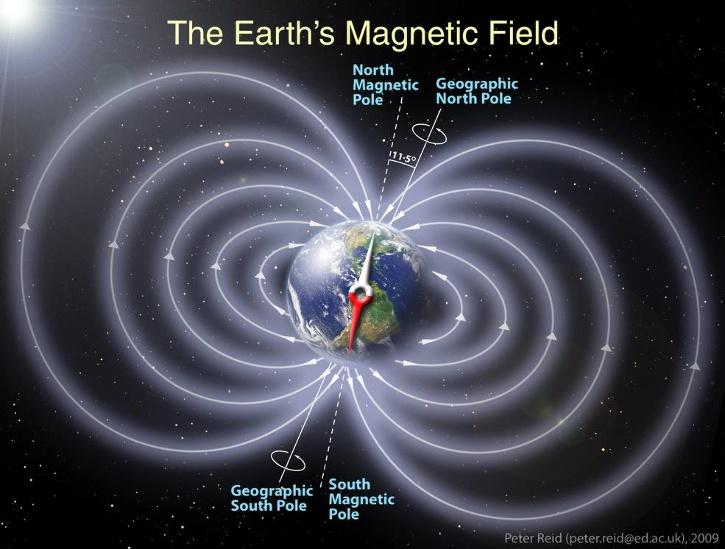

The Earth’s spin around the invisible axis–running through the center of Earth’s mass–is dependent, in part, on the distribution of weight around the globe and it shifts just like a spinning top, which starts to lean and wobble as its rotational axis changes.

“Earth’s polarity is not a constant,” NASA said in an explainer on polar shifts. “Earth has settled in the last 20 million years into a pattern of a pole reversal about every 200,000 to 300,000 years, although it has been more than twice that long since the last reversal.”

The magnetic north pole has been creeping northward by more than 600 miles since the early 19th century–which is when explorers first pinpointed its location–it is moving faster now migrating northward about 40 miles per year, as opposed to about 10 miles per year in the early 20th century, the space agency said.

During the mid-1990s, melting glaciers redistributed so much water that it changed the direction of the routine “polar wander” to not only turn eastward but also accelerate, the researchers said in a statement.

The study noted that the average drift speed between 1995 and 2020 increased about 17 times from the average speed between 1981 and 1995.

The researchers found that the contributions of water loss from the polar regions is the main driver of polar drift, with contributions from water loss in nonpolar regions, which explains the eastward change in polar drift.

Vincent Humphrey, a climate scientist at the University of Zurich, said this evidence reveals how much direct human activity can have an impact on changes to the mass of water on land.

The analysis revealed large changes in water mass in areas like California, northern Texas, the region around Beijing and northern India, areas that have been pumping large amounts of groundwater for agricultural use.

The recent change to the Earth’s axis isn’t large enough to affect daily life. Humphrey said It could alter the length of day, but only by milliseconds.

Article Credit: indiatimes