The Indian government is hoping its recent notification allowing the registration of electric vehicles without batteries finally ends the hesitation over battery-swapping. It has, however, sparked a tug of war in the sector over battery safety and standards.

For an electric vehicle (EV), a battery is like its central nervous system. A good battery can ration power supply to the vehicle, generate data-based feedback on performance, and prevent an EV from flaming out before its time. Without the right battery, an EV is little more than a flimsy metal frame. Buying an EV without a fitted battery would be a bizarre idea for any customer.

Not for the Indian government, though. On 13 August, the Ministry of Road Transport and Highways (MoRTH) issued a notification allowing the sale and registration of EVs without batteries. Batteries, it said, can now be independently registered and sold.

The timing of MoRTH’s notification was probably no coincidence. With the Covid-19 pandemic having decimated all types of auto sales, it fits in well with a renewed interest in EVs and personal mobility options. EV companies like Hero Electric, Okinawa, and Ather have signed up for innovative sales models; e-commerce giants Flipkart and Amazon have pledged to make a significant portion of their delivery fleets electric.

“The government is coming good on its promise to reduce the upfront cost of EV ownership,” says Priyank Agarwal, vice president of strategy and business development at Exicom, a Gurugram-based energy management company. Cleaving the battery from the vehicle halves the upfront cost of an electric two- or three-wheeler. “It will unlock new business models and let consumers source batteries directly from battery manufacturers, instead of just vehicle makers,” adds Agarwal.

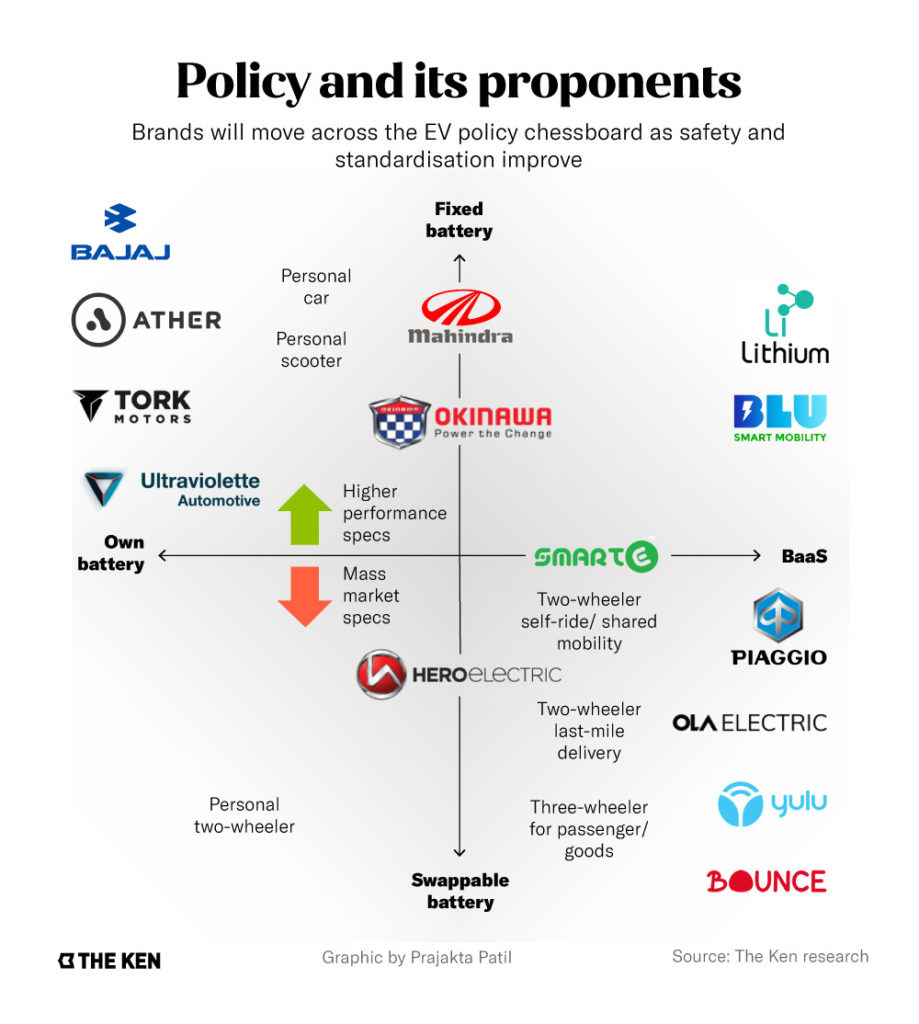

The notification, say industry experts, is also a clear signal in favour of battery-swapping. An alternative to regular charging, swapping can reduce the recharge time from two-to-six hours to a few minutes. This logic, coupled with the allure of the low upfront price, is the main pitch for companies that offer batteries as a service (BaaS), such as SUN Mobility and Ola Electric.

“Now, vehicles without batteries can enjoy the same privileges as those fitted with one,” says Ajay Goel, chief operating officer at SUN Mobility. The firm has tied up with the Indian Oil Corporation, India’s largest oil marketing company, to set up battery-swapping stations at its fuel pumps. SUN is hoping to piggyback on IOCL’s distribution network and increase its stations to double digits by the end of 2020.

EV manufacturers, however, aren’t enthused by the idea. On paper, they should be happy, since they can arguably sell more units at a cheaper cost. However, lurking beneath the lower sticker price is a whole range of sticky problems.

Like safety and guarantee. Currently, batteries attached to EVs come with a three- to five-year warranty. “The battery is crucial to an EV’s performance,” says Jeetender Sharma, founder and managing director of Okinawa, one of India’s largest electric two-wheeler makers. “How can we guarantee performance from an external battery?”

OEMs also don’t appreciate being left out of the equation. If a battery is the most valuable piece of the puzzle, taking it out means OEMs don’t get to charge for it or replace it. OEMs like Mahindra Electric, which have built-in batteries in their electric three-wheelers, will especially be at a disadvantage.

There are other thorny issues, too. For one, the goods and services tax (GST) on EVs is 5%, while it’s 18% on batteries. More crucially, there is no clear incentive structure for customers—individuals and fleets—to buy vehicles without batteries.

An innocuous MoRTH announcement is hardly the clarion call for a battle royale. But it does set the stage for a tug of war over how EVs will be bought and sold in the future. Between OEMs and BaaS providers, two different types of business models and incentives, are at loggerheads.

Their target is the same, though—to control the battery standard.

Customer appeal

The advantages of the new MoRTH notification for consumers are clear. They can now buy electric two-wheelers at half the cost—Rs 50,000 ($680) instead of the average Rs 1.2 lakh ($1,630)—and swap batteries rather than charging. A family could now own two to three electric scooters without having to pay for multiple battery packs.

De-linking the battery from the vehicle could lead to strategic benefits for commercial, business-to-business (B2B) fleet owners, too. “I can now bring a battery manufacturer on board, who can supply far better batteries than an OEM,” says Goldie Srivastava, co-founder and chief executive of SmartE, India’s largest EV mobility platform. “I can promise them volume and, in turn, hold them accountable for battery performance.”

A majority of SmartE’s fleet is e-rickshaws, which ferry commuters to and from Delhi’s metro stations. But after first- and last-mile travel dried up during the pandemic, Srivastava doubled down on the deliveries side of his business.

The notification, says Srivastava, has shifted the power balance in favour of BaaS companies, which understand battery chemistry and integration challenges with different types of EVs. Contracts with independent battery manufacturers will also hold them responsible in case of battery damage. “The cell, battery management system, software, assembly of batteries can improve as BaaS companies directly evangelise their batteries to customers,” says Srivastava. “Vehicle OEMs, especially e-rickshaw manufacturers, have inadequate knowledge of how lithium-ion batteries work. They weren’t adding any of this value to the battery. They simply look out for their margins.”

However, delivery fleets with routes below 100 km don’t really need battery swapping stations, says Sameer Jaiswal, co-founder at FAE Bikes, a Bengaluru-based EV mobility company. According to him, the radius for B2B deliveries is as follows:

- 40-55 km a day on fixed routes for Flipkart and Amazon

- 60-65 km a day for small basket deliveries like daily groceries

- 100-120 km a day for food deliveries

“We’ve worked with vehicle OEMs to make custom tweaks to the scooters they supply,” says Jaiswal. For instance, custom-made e-scooters are designed to hold two batteries; a spare helps double the range and, hence, running time.

“A fleet owner or a B2B business can earn more from the same asset if they use swappable batteries: groceries in the day and food delivery in the night,” says Exicom’s Agarwal. Instead of too many custom tweaks, fleet owners like FAE Bikes and SmartE might benefit from simply swapping. But it all comes down to the unit economics of swapping versus charging.

Little hacks

“Every OEM should provide a custom toolkit, that makes it easier to switch between batteries of different swapping companies,” says Agarwal of Exicom. At the vehicle level, this toolkit could help EV customers shift battery networks from one BAAS provider to the other based on who gives better deals

With fleets, swapping is a complex three-way transaction between an OEM, a fleet operator, and a battery manufacturer. Srivastava fears this opens loopholes to exploit. For instance, fly-by-night operators, or those willing to cut costs, could pair an e-rickshaw or electric scooter with a cheaper, unstable lead-acid battery.

Goel of SUN Mobility, however, is quick to dismiss this concern. The new notification, he says, doesn’t change the fact that each battery and vehicle combination has to be independently tested and approved by India’s nodal auto testing agency, the Automotive Research Association of India (ARAI), before it can hit the road. Each combination can take months to get approved. “Even a slight change in the design of a battery or a vehicle will have to be newly approved by the ARAI,” says Goel.

Srivastava, however, believes the system could still be exploited. While vehicles can be tested with one battery, there’s no guarantee that the same battery will be used in the future.

Jaiswal concurs, saying that if swapping becomes a free-market operation, then his company might receive poorer-quality batteries in return for their own good quality batteries. “The swap guys won’t hold the better batteries for my vehicle, right?”

BaaS makes the cash, the fiefdom remains

The concerns over safety and quality are foils for the much larger challenge of standardisation. So far, the lack of a uniform battery standard has culled out fiefdoms in the EV sector. Before the MoRTH notification dropped, the tussle between BaaS providers and vehicle OEMs was real; each could cut the other out of their network.

Now, however, with the very real possibility that customers can buy vehicles without batteries, it puts OEMs on the backfoot.

For instance, when it comes to ensuring compatibility with different battery types, the onus is on OEMs to get their vehicles tested several times over with ARAI. Making vehicles without batteries also makes OEMs heavily dependent on a BaaS network.

If OEMs want a sizeable piece of the delivery-plus-battery-swapping pie, they would have to make structural changes to their vehicles. Arguably every battery type will come with its own integration challenges. Making these changes without a certain return on investment (ROI) on the vehicles, or the promise of a subsidy, would be challenging for OEMs, say industry experts.

OEMs’ reputations are at stake too, says Okinawa’s Sharma. When ARAI tests vehicles, they are benchmarked at a certain performance level because the battery, motor, and controller are all tested in unison. For instance, the kinetic energy from the motor, when braking, recharges the battery; if there’s too much current, says Sharma, it could damage the battery. “That’s why it’s important to source the battery from the vehicle OEM,” he says.

The relationship between BaaS players and fleet operators isn’t frictionless either. “Why should I let a network make money off my fleet?” says Amit Gupta, co-founder of EV mobility company Yulu. “Anyone looking to scale their operations will not get locked into one platform.”

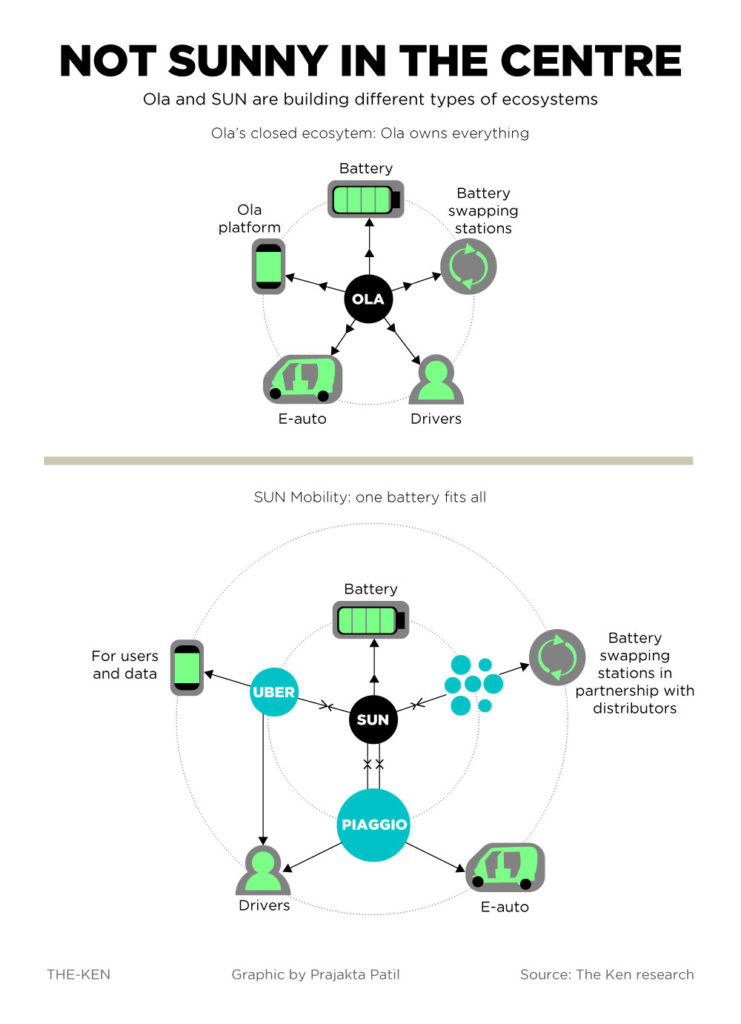

Yulu, too, is leasing out its e-bikes to delivery fleets during the pandemic, but the numbers, says Gupta, are in the single digits. This type of an arrangement, says Gupta, gives fleet owners less room for negotiating with a BaaS provider over price and quality. In vertically integrated models like Ola Electric—where the company provides the vehicle, batteries, and swap stations—the concentration of power is even more intense.

While Ola has chosen to create a unique stack of products, SUN Mobility is trying to combat the standards problem—and quell the fears of fleets like Yulu—by scaling the number of swapping stations. Building out this infrastructure is a two-step process.

For e-rickshaws and e-autos (three-wheelers), SUN is setting up stations within a targeted area that it calls a “micro-city”. Within that area, says Goel, SUN can map out fixed routes for these commercial vehicles and position their stations accordingly.

Planning for electric two-wheelers, though, is much tougher. “We will extend the micro-city concept to two-wheelers as well, but it will be a gradual ramp-up,” says Goel. “This isn’t a problem you simply throw money at. You need to encourage user adoption.”

A proxy standard

To leverage this new twist in policy, BaaS players currently have only two options: either fill towns and cities with swapping stations, or vertically integrate every part of the stack. Both options, however, require huge upfront capital and ample volume to justify the investment.

Globally, an example of an integrated stack—vehicle, battery, station—that has worked is Taiwan-based Gogoro. It operates over 90% of the swapping stations in Taiwan; it also plans to add another 1,900 to its existing 1,700-plus stations in 2020, called GoStations. Gogoro even sells its own electric scooters; and its batteries are now used by a few other OEMs like Yamaha and Aeon Motor. They, too, can swap batteries at GoStations.

“It’s the Apple model, where you own the whole ecosystem,” says Gupta. “No one else has been able to do that with EVs.” Ola Electric, arguably, has been trying to follow suit, but hasn’t grown its swapping network beyond the National Capital Region.

Things are a little more complex for India’s neighbour to the north. If Gogoro’s strategy has been market-driven, China’s EV sector has been largely driven by extensive government subsidies. And now, battery-swapping for electric cars has become a crucial element of its “ New Infrastructure” plan to combat the economic effects of the pandemic.

22 too much

Gogoro’s dominant EV business is also not without challenges. Kymco Motors, an incumbent Taiwanese auto giant, is close on its heels. Kymco plans to sell 500,000 scooters over the next three years, and is building a re-charging network for its scooters. Kymco plans to take this operation to 22 countries. It’s already invested $65 million in India’s 22 Motors

While cost and concentration of swap stations in only a few parts of the country are still issues, regional governments in China are tying up with EV majors like NIO to set up more stations. As of 20 August, NIO, one of China’s biggest electric car manufacturers, launched a scheme to subscribe to a battery plan separately when buying a car.

China’s EV market, though, isn’t out of the standardisation woods. Even with government support, OEMs like NIO and BAIC are still setting up individual, but large battery fiefdoms. Some signs of a thaw are visible. BAIC, NIO, and the China Automotive Technology and Research Center (CATARC) have hammered out a voluntary battery standard. This serves as a framework for developing swappable batteries in the future.

A loose federation of OEMs, BaaS providers, fleet owners, and battery manufacturers should emerge as a solution for India’s EV sector as well, says Gupta. “For entry-level two- and three-wheelers, the stakeholders can decide on a few common standards. This will facilitate choice. Customers aren’t going to get locked into one standard, and BaaS providers can swap batteries without worrying about a different standard coming into their network.”

However, this type of collaboration isn’t happening anytime soon. Instead, OEMs like Hero Electric are pressing on with investments in fast-charging over swapping. India’s EV sector is stuck in a weird limbo, where neither Gogoro-like OEMs have taken charge, nor has strong government action moved the needle forward. India’s EV policies have been a string of reversals and half-measures, strung together.

For this new announcement to count, the Indian government will have to design clear rules—and, possibly, a standard—around battery-swapping, which would bring the sector together. Right now, it’s only causing damaging and potentially lasting divisions.

Article Credit: the-ken

Pingback: Svitch MotoCorp All Set To Launch CSR 762, A Stylish EV For Young Biking Enthusiasts - SLSV - A global media & CSR consultancy network

Pingback: EV Battery Swapping Infrastructure in Indian Marketspace: Issues and the Way Ahead | IJPIEL