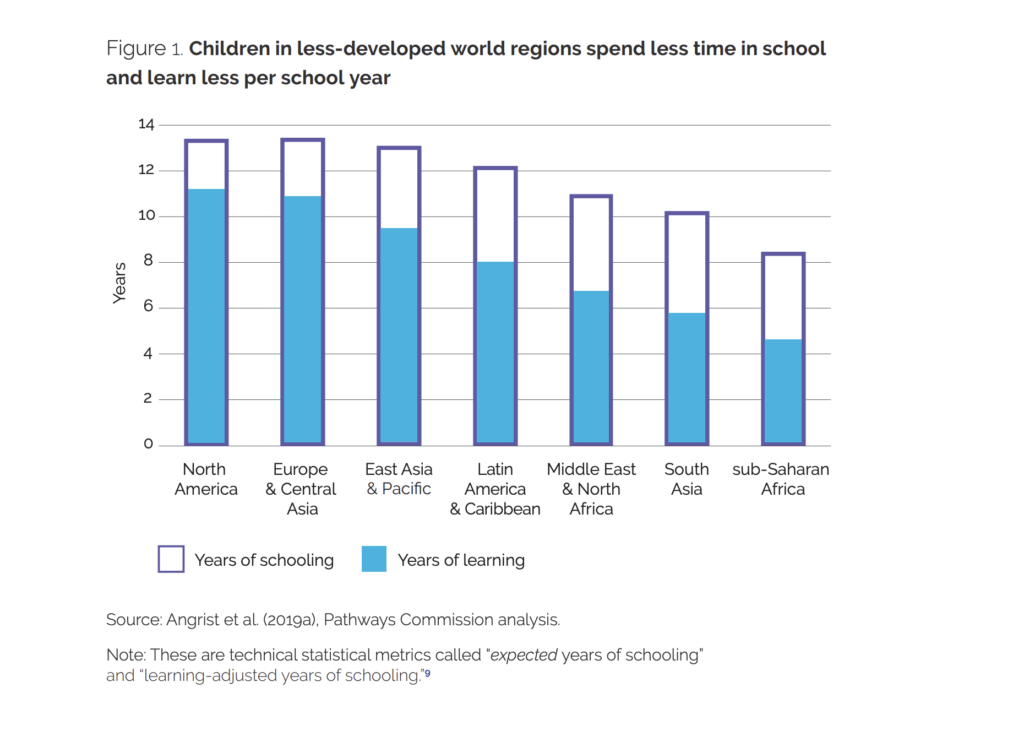

After decades of attempting to improve failing health and education systems in developing countries, the situation in many areas is still dire. In some sub-Saharan African countries, children achieve as little as 2.3 to 5 years of learning, despite typically spending 8 years in school. More than five million children still die before their fifth birthday. The old approach isn’t working, which is why it’s tempting to think that technology is the quick fix.

Artificial intelligence for medicine and educational technology (ed-tech) for learning are gaining popularity with both the public and investors. People are envisioning a future where children across the world can be taught through virtual reality and patients in remote areas will be treated by robots. Small-scale examples of success are being seized upon as justification for investing in any shiny new bit of tech, in the hope that it will be the one that makes all the difference.

But it’s dangerous to see the success of new technologies as inevitable. In developing countries, technological hype has driven expensive investments in hardware billed as silver bullet solutions. There have been programmes to give every child a laptop, but teachers have lacked the skills and digital training to use them so the computers end up locked inside drawers. High-end medical equipment has gathered dust in hospitals worldwide. Such investments have not only wasted money in countries on tight budgets, but have also created widespread misunderstanding of how best to invest in technological solutions.

New research that I have been leading has investigated why some quick fix programmes fail, and what it takes to succeed. The interventions that work do two things. They focus not just on hardware, but on the content, data sharing and system-wide connections enabled by digital technology. And they only deploy technology after careful consideration, and when it’s appropriate to tackle a real, identified problem.

A policy of buying a laptop for every child in Peru failed, while a similar programme in China succeeded – because computers were embedded within standard teaching practice and digital content was prepared.

In Uganda, the web-based application Mobile VRS has helped increase birth registration rates from 28% to 70% across the country, enabling decision-makers to track health outcomes and improve access to services for these children. It worked because it targeted the root of the problem – children weren’t getting treated and vaccinated because practitioners didn’t know they existed.

In Kenya, the Ministry of Education has rolled out a programme called Tusome, a literacy platform with digital teaching materials and a tablet-based teacher feedback system. Its huge success stems from the fact that it targets two pre-identified areas that needed improvement – access to learning resources and teacher performance.

These examples give hope that technology really could be the key to closing the health and education gap between rich and poor. But it has to be done right. The first step to large-scale improvement to health and education systems is the effective use of data. Data is the fuel of well-functioning digital systems, and there are some simple pioneering examples.

One approach is to use integrated dashboards that collect data for better decision-making. For example, both the Ghana School Mapping platform and the MoSQUIT mobile platform tracking malaria in India enable smarter resource allocation on a large scale. A community health workers’ programme run by Musoin Mali, which sends doctors to identify and treat patients in their homes in the most remote areas, has achieved the lowest child mortality rates in sub-Saharan Africa. Technology helped to scale up the programme as digital dashboards for monitoring drove productivity up.

Adaptive learning software that tailors learning based on data collected about a child’s performance is also showing huge promise. An example of this is MindSpark in India, which achieved an increase in maths performance of 38% in five months, with estimated costs as low as $2 a year when scaled up to more than 1000 schools. The technology empowers learners, tailoring lessons to their strengths and working on their weaknesses.

A similar concept is behind onebillion, a programme that has just won Elon Musk’s $5 million XPrize for Global Learning, and is being scaled up across Malawi with the Ministry of Education. Evidence has shown that the programme has the potential to close the gender gap in maths – a crucial step in the journey of giving girls better access to education and the job market.

So is tech really the answer? There are many reasons to be optimistic, but only if the potential for poor choices and failure is kept in mind every step of the way. Technology really could be a potential catalyst for massive positive disruption, but – perhaps paradoxically – this will only happen if it is implemented with care and caution

The new Pathways Commission report, Positive disruption: health and education in a digital age, highlights how technology, if properly harnessed, can be a transformative force for the poorest and most marginalised people. The new Pathways Commission report, Positive disruption: health and education in a digital age, highlights how technology, if properly harnessed, can be a transformative force for the poorest and most marginalised people.

Article Credit: WeForum