42% India’s land area under drought, worsening farm distress

About 42% of India’s land area is facing drought, with 6% exceptionally dry–four times the spatial extent of drought last year, according to data for the week ending March 26, 2019, from the Drought Early Warning System (DEWS), a real-time drought monitoring platform.

Andhra Pradesh, Bihar, Gujarat, Jharkhand, Karnataka, Maharashtra, parts of the North-East, Rajasthan, Tamil Nadu and Telangana are the worst hit. These states are home to 500 million people, almost 40% of the country’s population.

While the central government has not declared drought anywhere so far, the state governments of Andhra Pradesh, Gujarat, Karnataka, Maharashtra, Odisha and Rajasthan have declared many of their districts as drought-hit.

Failed monsoon rains are the primary reason for the current situation. The North-East monsoon, also known as ‘post-monsoon rainfall’ (October-December) that provides 10-20% of India’s rainfall, was deficient by 44% in 2018 from the long-term normal of 127.2 mm, as per data from the India Meteorological Department (IMD). This compounded the rainfall deficit in the South-West (SW) monsoon (June-September) that provides 80% of India’s rainfall, which fell short by 9.4% in 2018–close to the 10% deficit range when the IMD declares a drought.

India has experienced widespread drought every year since 2015, Mishra said, with the exception of 2017. As the El Nino–the unusual warming of the equatorial Pacific Ocean that makes Indian summers warmer and reduces rainfall–looms over the 2019 SW monsoon, pre-monsoon showers (March-May) this year have also been deficient. India has received 36% less rainfall than the long-term average between March 1 and March 28, 2019, as per IMD data. The southern peninsular region recorded the lowest, a deficit greater than 60%.

Lower rainfall has reduced water levels in reservoirs across the country. The amount of water available in the country’s 91 major reservoirs has gone down 32 percentage points over five months to March 22, 2019. In 31 reservoirs of southern states, water level has gone down by 36 percentage points over five months.

The drought could further worsen farm distress, exacerbate groundwater extraction, increase migration from rural to urban areas, and further inflame water conflicts between states and between farms, cities and industries.

Yet, the latest drought manual issued in 2016 by the central government makes the process of declaring drought long and difficult, experts say, with the result that drought may go officially unannounced. This means relief measures such as drinking water supply, subsidised diesel and electricity for irrigation, increased number of days of insured work under National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (NREGA) are not taken. And elections may further delay government acknowledgement and action.

This is the first of a six-part series on drought and its impact in five affected regions–Andhra Pradesh, Gujarat, Karnataka, Maharashtra and Rajasthan.

Extent and severity of drought

The parts of the country facing drought have been divided into six categories—Exceptionally Dry, Extremely Dry, Severely Dry, Moderately Dry, Abnormally Dry and No Drought, as per DEWS.

About 6% of the land area of the country is currently in the Exceptionally Dry category, which is nearly four times the 1.6% area at the same time last year. The area in Extremely and Exceptionally dry categories is 11% of the entire country, more than double the 5% area in March 2018, as per DEWS data.

DEWS provides updates based on rainfall, runoff and soil moisture–measured by standardised precipitation index (SPI), standardised runoff index (SRI), and standardised soil moisture index (SSI), respectively. Along with providing daily updates from across the country, it also provides a short-term, seven-day forecast.

The Manual for Drought Management 2016 considers two factors as indicative of a drought:

– The extent of rainfall deviation (depreciation)

– The consequent dry spell

To assess the extent of drought, the following impact indicators are studied: agriculture, remote sensing, soil moisture and hydrology. Each impact indicator has various levels of severity.

To be categorised as severely drought-hit, at least three of these four must indicate drought. In case of a moderate drought, at least two (in addition to rainfall) must check out. If only one impact indicator (in addition to rainfall) checks out, the area is not considered to be drought-affected.

Once indicators show ‘moderate’ or ‘severe’ drought, the state government conducts a sample survey on the ground. If this report establishes a ‘severe’ category drought, a memorandum of assistance is submitted to the National Disaster Response Fund (NDRF) for mitigation and relief.

Rainfall data over the past century indicate that India has faced a severe drought every eight or nine years.

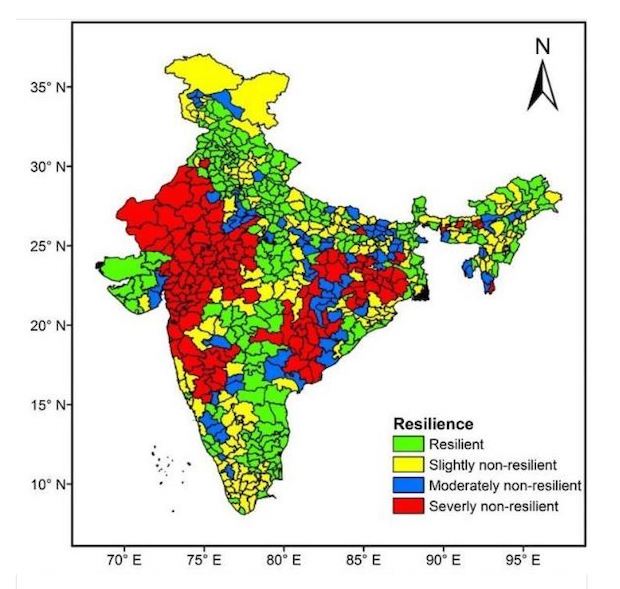

Yet, 60% or three of every five districts in India are not prepared for drought, said a September 2018 paper published jointly by IIT-Indore and IIT-Guwahati. It found 241 (38%) of 634 districts it studied to be drought-resilient.

At least 133 of these 634 districts face drought almost every year; most of them are in Chhattisgarh, Karnataka, Maharashtra and Rajasthan, said the study that assessed how efficiently districts use water when dealt with hydroclimatic disturbances.

The study also found that only 10 of 30 states and union territories had more than 50% drought-resilient area. Tamil Nadu was the best performer, with 56.74%, followed by Andhra Pradesh (53.43%) and Telangana (48.61%), while Karnataka (17.38%) and Kerala (19.13%) were at the bottom of the list. Among the northeastern states, Assam at 20.72% had the lowest percentage of resilient area.

Dwindling rainfall

Since the SW monsoon of 2018, India has received less-than-average rainfall, with June-September rains being 9% deficient and the post-monsoon October-December rains 44% deficient.

Between January 2019 and February 15, 2019, there was no rain in 23% of the total 660 districts surveyed, which extended to 46% below normal in March, data from IMD show. This is not unusual in itself, but combined with last year’s deficit, this has made the situation dire, Mishra said.

Lack of rainfall is forcing regions to use up their water reservoirs. In 31 reservoirs in the southern states, water availability stands at 25% of total capacity, which has gone down by 36 percentage points over five months from 61% of the capacity in November 2018.

Effects of climate change

Climate change is amplifying the impacts of drought, researchers say.

The climatic conditions that led to drought and famine in the 1870s could make a similar drought worse if the current state of global warming is taken into consideration, Deepti Singh, assistant professor at the School of the Environment at Washington State University (WSU), US, said in a research paper, ‘Climate and the Global Famine of 1876–78’, which studied the Great Drought in India between 1875 and 1878.

“Today, we live in a much warmer world than we did in the 1870s. So, a warmer climate can have adverse effects on droughts making it more extreme,” Singh told IndiaSpend. She said droughts during 1876-77 and 2015-16 were triggered by extremely strong and long-lasting El Ninos. “However, droughts have continued to persist in India post-2016 despite a change from El Nino conditions, which to me is an indication of the effect of global warming,” she said.

The drought in parts of India in 2018 has been coupled with flash floods in Kerala and Karnataka; while Tamil Nadu and Odisha have faced cyclones Gaja and Titli, respectively.

These extreme weather events are linked with increasing global temperatures. The earth has warmed by 1 degree-Celsius (°C) from pre-industrial times (1800s) due to human activities, said the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)’s report released in October 2018 and revised in January 2019. If global warming is not stopped at 1.5°C increase, it would cause heavy precipitation in some parts of the world as well as frequent and intense droughts in other parts.

Changes in monsoon patterns due to increased temperatures would make droughts and floods more common in many parts of India. Frequent droughts are particularly likely in north-western India, Jharkhand, Odisha and Chhattisgarh, according to a 2013 World Bank study.

The Ganges, Brahmaputra and Meghna river basins, which serve more than 650 million people, are likely to experience both droughts and floods more often, this 2015 studypublished in the journal Environmental Science said.

Farm economy to bear the brunt

With 50% of India’s population dependant on agriculture and more than 50% of the cultivable area being rainfed, the farm economy could take the hardest blow from the ongoing drought, particularly as government programmes–such as farm insurance and irrigation infrastructure–are floundering.

In addition to the impact on farmers, landless agricultural labourers will lose employment, R Ramakumar, National Bank for Agricultural and Rural Development (NABARD) chair professor at the School of Development Studies at the Tata Institute of Social Sciences(TISS), told IndiaSpend. “Agricultural labourers anyway get hardly 150-160 days of labour a year and this [drought] is going to make it worse,” he said.

Although loans taken by farmers from banks are insured on payment of a small premium, entitling them to compensation in case of crop failure, farmers who take loans from informal moneylenders end up badly hit by bad harvests, said AV Manjunath, assistant professor and an expert on agricultural water management at the Institute for Social and Economic Change (ISEC).

However, the central government’s scheme to insure crops against unpredictable weather, the Pradhan Mantri Fasal Bima Yojna (PMFBY), has been criticised for making meagre payouts and benefiting only insurance companies, as IndiaSpend’s Factchecker.in reportedon February 26, 2019.

In addition to bad implementation, only 29% of sampled farmers were aware of PMFBY, a PTI report published on August 20, 2018, and based on a survey conducted in eight Indian states by BASIX, an institution that promotes livelihoods, said. Of these, only 12.9% could get crop insurance. The farmers cited several challenges for availing crop insurance.

Very few households involved in crop production were insuring their crops, the Economic Survey of 2018 had pointed out. In the case of wheat and paddy–two of the most popular crops–less than 5% of agricultural households had insured their crops.

The difference between the premiums received by insurance companies and the compensation paid to farmers was nearly Rs 16,000 crore in two years, The Wire reported in November 2018. In 2016-17, around 57 million farmers had joined the scheme but the following year, 8.4 million (14%) had exited it.

The impact of the drought may be less acute in areas where irrigation facilities are available, Ramakumar said. But net irrigated area is only 34.5% of the total cultivated area in India, as the Economic Survey 2017-18 also noted.

In 2014 when the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) came to power, the government promised it would complete 99 irrigation projects by 2019 under the Pradhan Mantri Krishi Sinchayee Yojana (PMKSY). However, 74 of these are still without field canals, reported The Telegraph in December 2018.

Of the 16 national water projects brought under the Accelerated Irrigation Benefits Programme (AIBP), only five were under way, a Comptroller and Auditor General (CAG) report released in 2018 said. Work on the remaining 11 is yet to begin. This delay has resulted in cost escalation of Rs 224.54 crore for these 11 projects, while the irrigation potential achieved from the five ongoing projects is only 37%, without any drinking water or power generation arrangements.

The CAG audit sampled 118 major to medium irrigation projects for a decade ending 2017 and found that the cost overrun for 84 of them was Rs 120,772 crore, enough to buy 72 Rafale fighter jets, IndiaSpend reported on February 25, 2019.

Of the 201 larger irrigation projects, 70% were not completed and 55.5% of irrigation target was not achieved, another CAG report released in January 2019 said. The irrigation potential achieved from small schemes was even lower–22% of the target.

‘Big’ water projects do not reap any benefits, Himanshu Thakkar, coordinator at the South Asia Network on Dams, Rivers and People (SANDRP), told IndiaSpend. “Big government projects like irrigation projects, river linking projects, big hydro and other such mega projects are examples of schemes and programmes that are not helpful,” he said, adding that these in fact worsen groundwater depletion.

The adoption of micro irrigation techniques, on the other hand, has helped manage drought in north Karnataka, enabling agriculture in drought-prone areas such as Kolar and Chikkaballapur, Manjunath of ISEC said. However, he said, these projects need to be scaled up as surface water is disappearing at a swift pace.

Only 7.73 million hectares (mha) of India’s estimated 69.5 mha with micro-irrigation potential have actually got it–drip Irrigation over 3.37 mha and sprinkler irrigation over 4.36 mha, IndiaSpend reported on June 25, 2018.

Drought-induced migration

Farmers asked about their biggest problems named flood/drought (13%), low productivity (11%) and irrigation (9%), in a study conducted by the Centre for the study of Developing Societies (CSDS) released in March 2018, which was based on responses from 274 villages spread across 137 districts in 18 states. Although 79% of the sample population depended on agriculture as their main source of income, 62% said they would quit farming for a good job in the city.

The southern highlands between Bangalore and Chennai are going to be among the major hotspots for internal migration in the world, said a 2018 report by the World Bank, ‘Groundswell: Preparing for Internal Climate Migration’.

In Bengaluru, most migrants come from north Karnataka districts such as Belgaum, Dharwad, Raichur and Gulbarga, which have been experiencing droughts, said Harini Nagendra, an ecologist and professor of sustainability at Azim Premji University (APU), who has studied the lives of migrants around Bengaluru’s lakes. “[I]n places where these migrants are from, agriculture is disappearing with the dwindling water resources,” she said.

There will be more than 143 million climate migrants across Sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia and Latin America by 2050, with about 40 million or 28% coming from South Asia alone, as per the World Bank report.

Droughts can also have consequences for electricity provision when countries rely a lot on hydropower, said Sebastien Gael Desbureaux, an economist with the World Bank who has researched water quality and availability. India gets 17% of its electricity from hydropower. “When we listen to epidemiologists, they emphasize that the lack of water favours the spread of disease as people have less water for hygiene. Also, when water is scarce, the concentration of pollutants increases significantly, with direct health effects,” he said.

Yet, Indian cities themselves are facing water shortage–almost 21 cities including Bengaluru, New Delhi, Chennai and Hyderabad will run out of groundwater by 2020, affecting 100 million people, said the Composite Water Management Index (CWMI) published by the Niti Aayog in June 2018.

In all, 600 million Indians–or half the population–face high to extreme water stress, as per CWMI. Up to 75% of households do not have drinking water on-premise and by 2030, 40% of the population will have no access to drinking water.

Groundwater disappearing

Nearly 65% of irrigation supply and 85% of drinking water supply is supported by groundwater in India, said a draft report on the proceedings of the South Asia Groundwater Forum (SAGF). The forum convened by the World Bank in partnership with the International Water Association and the Indian government was held on June 1-3, 2016, in Jaipur, Rajasthan.

The ongoing drought could exacerbate the extraction of groundwater and further its depletion, especially in areas without piped water that rely on groundwater extraction, Nagendra of APU said.

Nagendra illustrates with the example of Bengaluru where borewells do not find water even at depths of 800 ft, and generally deeper borewells have higher chances of arsenic and fluoride contamination. Large, open wells where people drew water have completely dried up, she said, adding that open wells can be recharged with rainwater but borewells cannot.

The water shortage in many parts of the country can fuel interstate and international conflicts in India, IndiaSpend reported on June 6, 2018. Ongoing conflicts include:

- Cauvery river dispute between Karnataka and Tamil Nadu

- Krishna river dispute among Andhra Pradesh, Maharashtra, Karnataka and Telangana

- Narmada river dispute among Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh and Maharashtra

- Ravi and Beas river dispute between Haryana, Punjab and Rajasthan

- Disputes between India and China for the water distribution of 10 major rivers originating in Tibet

Effective drought proofing, management and monitoring

The ongoing drought situation has gone largely unremarked because of a delay in the official declaration of drought by state governments. This has implications not only for the ongoing drought but also for the future, given India’s rapid groundwater depletion, decline in average rainfall and increasing dry monsoon days, as the Economic Survey of 2018 acknowledged.

States such as Karnataka have opposed the latest drought management manual that came out in December 2016, saying it made it difficult to establish the severity of drought and would drastically reduce assistance from the Centre’s National Disaster Relief Fund (NDRF).

The manual obligates states to assess numerous parameters, based on which an area can be declared drought-hit and assigned a ‘severe’, ‘moderate’ or ‘normal’ category. Gathering data and analysing it is really difficult, said Mishra of IIT-Gandhinagar and DEWS.

The parameters include rainfall, soil moisture, agriculture, hydrology, and the state of crops, which are further sub-divided into parameters, making for a detailed and laborious process that state governments find difficult to complete quickly. As a result, “[M]ost of the states take action and declare a drought when there are incidents of crop failure and groundwater table has depleted. This is when you start witnessing the impacts of droughts and this is too late most of the time,” Mishra said.

Also, sometimes an entire state does not face drought but smaller regions, often constituting 10% or 20% of a state’s area, face exceptionally severe drought. In such cases, the Centre overlooks the severity of the drought in a limited area and the state gets no assistance from the National Disaster Response Force, Mishra said, adding that the management and handling of drought needs “a paradigm shift”.

In addition to a system for early warning, at least in drought-prone states, robust indicators should be delineated along with a clear methodology. “When there is consistent monitoring for each district and some districts start showing abnormalities, you easily get the information,” he said.

Article credit: Business Standard